|

Red-crowned Alert

Tang dynasty poets waxed lyrical about them; Ming dynasty emperors coveted paintings of them; Qing

dynasty artisans emblazoned their images on the finest porcelain. Throughout much of Chinese recorded history they have been synonymous

with longevity and with the best of luck. Sadly though, the Red-crowned Crane's own luck appears to

be running out. If the dramatic decline in wintering-numbers witnessed in recent years continues,

the Red-crowned Crane's "Western Flyway" population could become extinct before the end of the decade.

In other words, the species would disappear as a migrant and wintering bird across a vast swathe of China.

If that happens, then the species' breeding strongholds

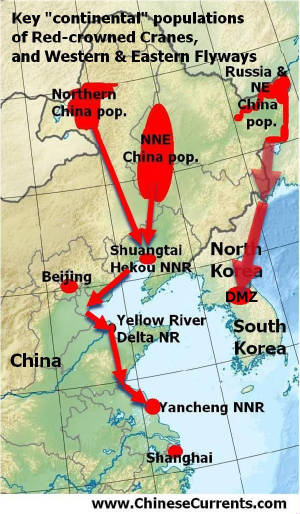

would be reduced from four to just two: The non-migratory Japanese population (which, at more than 1,300

birds, has become the largest of the population groups); and the Russia and NE China population, of just over

1,000 birds, which migrates via the "Eastern

Flyway" to winter on the Korean peninsula (mainly at Cheorwon in the DMZ, but also in three other locations). In

the 1990s, this Eastern Flyway population was outnumbered by Western Flyway birds by a ratio of 3:1. The accepted

wisdom is that the ratio is now 1:2; and nudging ever closer to 1:3, and a complete reversal

of fortunes. Su Liying

and Zou Hongfei in their 2012 paper described the most recent speed

of decline in the Western Flyway populations as "frightening". Except

for "15-75" birds that winter at the Yellow River Delta Nature Reserve, in Shandong province, and perhaps a

few stragglers elsewhere, the entire Western Flyway population winters at one location: at Yancheng National

Nature Reserve (NNR) in Jiangsu province. The fall in the Yancheng numbers is, therefore, the focus

of this article: There were 1,128 Red-crowned Cranes at Yancheng in the

winter of 1999-2000. Nine years on, in 2008-2009, the number wintering

there had fallen to around 400 birds. Su and Zou believe that, "Most recently the decline has occurred more quickly, by 50–150 birds per winter.” I of course knew that wintering numbers had fallen dramatically in recent years before I boarded the Yancheng-bound public bus in

Shanghai, last week. But I only had the vaguest idea of the

root causes of the China-wintering-population's sad decline. I had thought that the drying-out of

the breeding grounds in northern and north-eastern China was largely responsible. Four hours later, I arrived at the city of Yancheng. Less than one hour taxi-ride after that, I was watching

birds at Yancheng NNR. I was also beginning to reshape my opinion of the issue. But it was not until my second day there, and

only after I had seen a vast area, that I came to the conclusion that the people who have been responsible for the management

policy of Yancheng NNR must take at least a slice of the blame for the dangerously rapid decline of the Western Flyway

population. To put it bluntly, the extent

of the deterioration of the habitat, since my visit there in December 2001, was shocking. Where 11 years ago there were reed beds, there

were now shrimp and fish ponds. Miles and miles of them.

On returning to Beijing, I would spend two days researching the local management-policy changes that had led to

this. On the second day of my digging,

I found something that was alarming to say the least:

Buried deep in the vaults of a Chinese search engine, I found a report written by Xiao Hua with the headline, "Yancheng

Red-Crowned Crane Emergency". According

to Mr Xiao, an investigative reporter, the Yancheng nature reserve authorities signed

a 5 year contract with one named person to lease out 14,918 mu [9.95 square kilometers] of wetland for conversion to aquaculture

[shrimp and fish farming]. The contract period was from 1st January 2008 to 31st December 2012.

Mr

Xiao reported that the reserve made 2 million yuan per year from this deal, and that the person who had bought

the right to use the land, had then sub-leased it to local farmers, making a sizeable profit. One of many questions I haven't been

able to find an answer to so far is, what has happened to this land following the expiry of the lease? Suffice to say that the reserve's management have a

golden opportunity to restore this land to its former glory.

Another key issue is the land use policy relating to agriculture in the area. To the north of the reserve, there are

dozens of square miles of fields. It is there that I took the photograph of the family of four Red-crowned cranes

that appears at the top of this report. Although it was of course wonderful to watch these birds, my experience was sullied

by the knowledge that Red-crowned Cranes

are increasingly resorting to looking for food on the vast number of fields that surround the reserve, because they are

being squeezed out of their preferred habitat Indeed, Su and Zou, citing Ke et al [2011] state that, from

1988 to 2006, between 53.8 and 66.91 per cent of Yancheng NNR's wetland was lost to

“aquaculture, diking, and farming”. As is well documented, human encroachment of wetlands is

extremely bad news for wildlife. In China, trapping and poisoning

often go hand-in-hand with farming and aquaculture. In their 2012 paper, Su and Zou list the poisoning incidents of

Red-crowned Crane in China that have made it into the public domain. As they point out, these

reports are possibly just the tip of the iceberg: At Yancheng, in

13 years (from winters of 1995-95 to the winters of 2008-09), 61 birds were found poisoned.

33 of those 61 birds died. In the winter of 2008-09, seven birds died (all of those that

were reported to have been poisoned). On my visit to Yancheng last week, I found more than a dozen empty bottles of poison

(my photograph appears here). The bottles were on a path next to a dike, only tw o hundred yards away from a large flock of Common Cranes [about 1,200 were in the vicinity] and about 20 Hooded Cranes; and

only 1 mile north of where I had photographed the Red-crowned Cranes the day before. o hundred yards away from a large flock of Common Cranes [about 1,200 were in the vicinity] and about 20 Hooded Cranes; and

only 1 mile north of where I had photographed the Red-crowned Cranes the day before.

Enquiries on Sina Weibo [China's most popular Twitter-like microblogging site] revealed that this poison was an

agricultural pesticide, and the consensus was that it had been used to treat crops and not to target cranes or other

birds. This may well be the case. But, the important point to note is that, for more

than 5 years now, the use of any agricultural pesticide has been banned in this area [In

October 2007, the Xinhua news agency reported that, "The use of fertilizers, pesticides and other chemicals has also

been banned in about 6,000 hectares of farmland surrounding the reserve." ]. Another question this raises is, why had the

bottles not been taken away by patrolling wardens, to be used as evidence to prosecute the farmers who are responsible for

the spraying?

On my first day at Yancheng, in addition to the family of four Red-crowned Cranes, I saw another party of three,

that were also feeding on farmland. On the second day, I saw another party of three near to the reserve

centre, and two adults three miles to the east of the reserve centre (incongruously searching for food on a drained

shrimp pond).

In summary, in two days birding there, I saw a less-than-grand total of 12 Red-crowned Cranes. That's not

to say that there are not four, or even five hundred more in the core area of the reserve, the part that the public quite

rightly isn't allowed to access. In 2001, the cranes could be easily seen from the public

vantage points. On Christmas Eve 2001, I saw about 100 Red-crowned Cranes.

On Christmas Day 2001, my present was the incredible sight of an estimated 230 Red-crowned Cranes. How many birds were actually there this winter, I enquired. "Hundreds," I was told. "How many hundreds?" I asked.

"Hard to say," was the reply.  Sadly, I saw more Red-crowned Cranes in what the Jiangsu tourist web site describes as "...a small zoo where the

wounded birds and animals are hosted for treatments..." than I saw in the wild. Sadly, I saw more Red-crowned Cranes in what the Jiangsu tourist web site describes as "...a small zoo where the

wounded birds and animals are hosted for treatments..." than I saw in the wild.

There were 20 Red-crowned Cranes in the

"small zoo".

Taking the website at its word, I looked for signs of injury. The caged birds (four to a cage mostly) looked to be in

fine fettle. At times, some birds would fly around the cage, all the way up to the netting on the ceiling. But

they did seem to be very wary of humans (when three tourists approached them to get some snaps). Then I saw the sign: "Red-crowned

Crane taming [this word can also be translated as "domesticating" ] centre." "...Red-crowned Crane captive breeding... In

the beginning 3 eggs from the North-East of China... Failed for many years... First breeding success here in

the year 2000 ... 80 birds reared successfully here... Enjoy crane dancing... flying displays... and performances in

the arena..." Clearly the

sign raises many more questions than it provides answers. As I was composing myself, I noticed the terraced seating area overlooking the display area.

I looked at the Red-crowned Cranes in the cages. And I stared at the construction site that will, when complete, create

a semi-circle of cages opposite the terracing that has a seating capacity of a few of hundred people. 7 cages occupied. 18 more being

built. Room enough, when finished, for 100 Red-crowned Cranes. Sadly, the "small zoo", is about to become a big zoo. As well as the stars of the show, there is

also a line-up of warm-up acts:

In another area there were cages with 4 White-naped Cranes;

4 Common Cranes; 2 Demoiselle Cranes; 4 Siberian Cranes; 2 Hooded Cranes; and 2 Oriental White Storks, as

well as another 8 Oriental White Storks and a docile Red-crowned Crane on what the website describes as a "waterfowl

lake" - together with a Black Swan, and various other domesticated waterfowl. I then began

to grasp the economics of spending tens of millions of dollars on an enormous (and yet-to-be opened) visitor centre: Wild wintering cranes are not a popular

tourist attraction. They are extremely wary of humans; and it is cold in Yancheng in winter... sometimes very cold. But the promise of a ringside seat

to watch "crane dancing" in the warm Jiangsu spring sunshine is bound to pull in the crowds. And Yancheng NNR has access

to potentially massive crowds within one hour's drive. Yancheng is not only famous for its nature reserve,

it is also a prefecture level city with a population of 8.2 million people. The urban centre of which

is less than an hour's drive away from the reserve centre. It's also a city that doubled its GDP during 2006-2010 [The period of China's 11th 5-year

plan]. During that period the average per-capita disposable income of Yancheng's urban residents increased by a whopping

13.5 per cent per year. Large increases in disposable income above a certain level feed through to rapid growth

in car ownership, which in turn translates to greater expenditure on local tourism. Other cities in China are

also channelling investment into Red-crowned Crane so-called "eco-tourism" [a term that is used by the Yancheng

city government]. There were at least 10 Red-crowned Cranes in captivity at the “wetland zone” of a “theme

park” in Guangzhou, Guangdong province in 2011, for instance. It is not suggested that these birds came from Yancheng. It is important, however, to find out where all the captive Red-crowned

Cranes are; as well as their age, condition and of course to also pinpoint where they came from, and how they got there.

It is also important that one independent organisation (that doesn't have a financial interest) is able to coordinate

this, to ensure that there is a net return of the birds to, as opposed to a net removal from the wild.

I suggest that Rang Hou Niao Fei [Let migrant birds fly], an NGO that has done wonderful work protecting wild birds

in China, steps in. I do not know how many Western Flyway birds, thus far, have been returned

to the wild from captive breeding projects, but I suspect it is very few. But I do know

that the captive breeding and rearing of Red-crowned Cranes at Yancheng has nothing to do with the reserve's main

conservation goals and responsibilities. Captive breeding is not the solution

to this population's dire problems. Clearly, there is only one solution: To safeguard

existing habitat and restore and secure lost habitat on the breeding, staging, and wintering grounds. Only then will this

precious population of Red-crowned Cranes be pulled back from the brink.  .

|