|

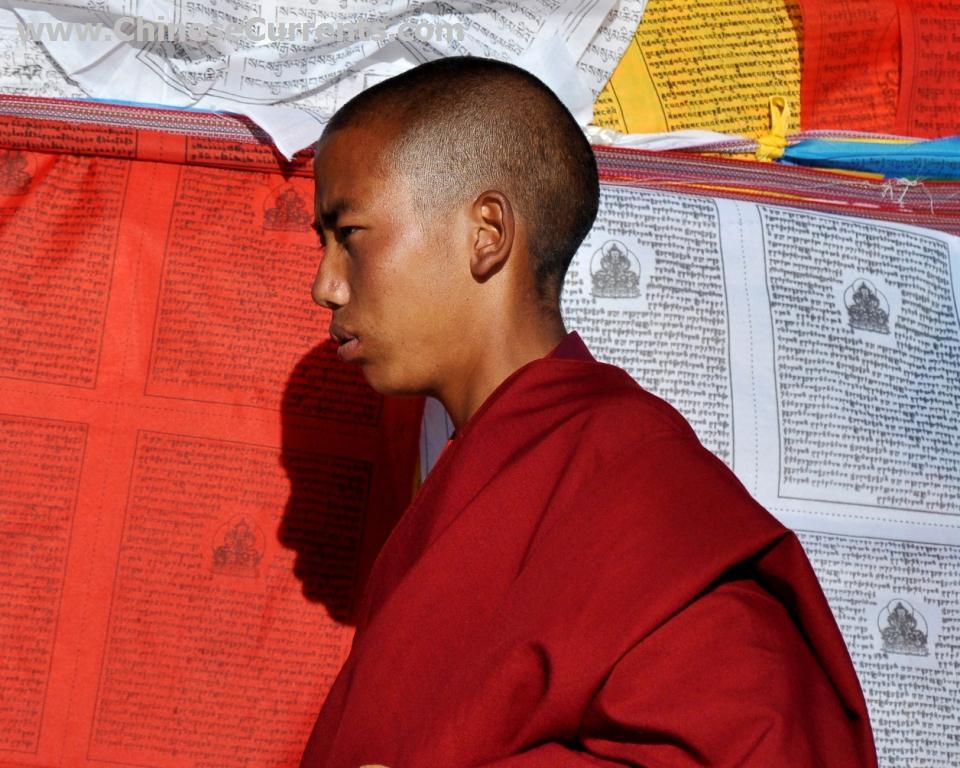

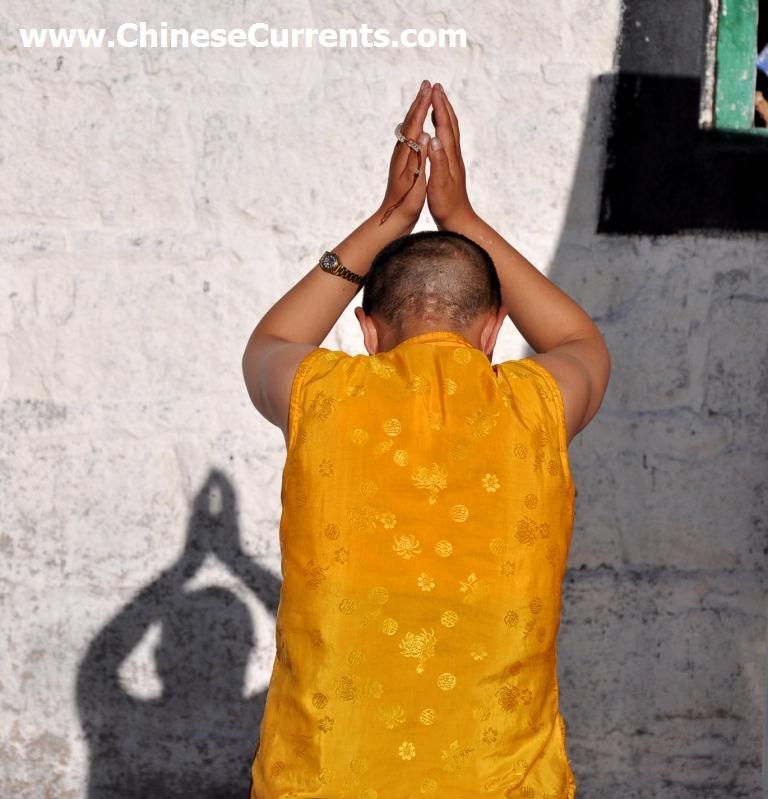

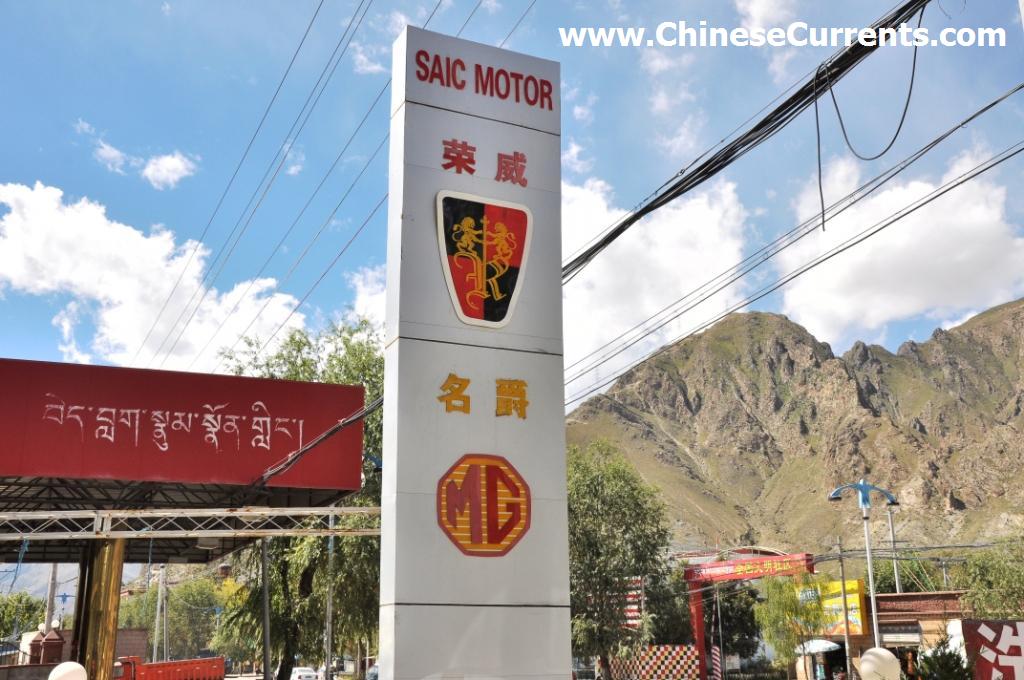

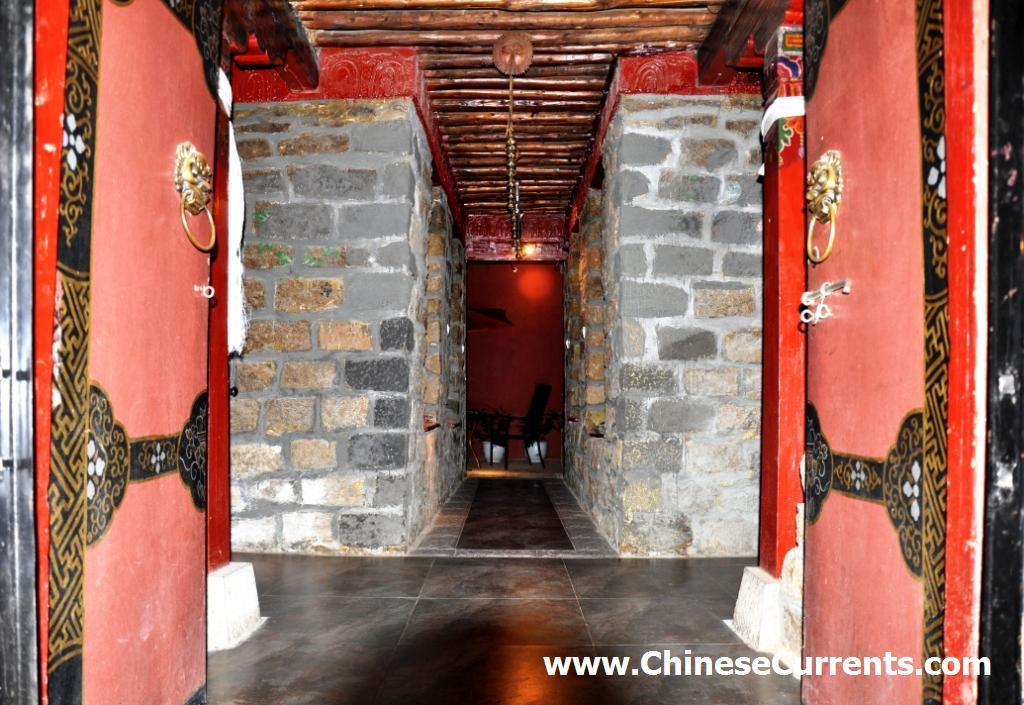

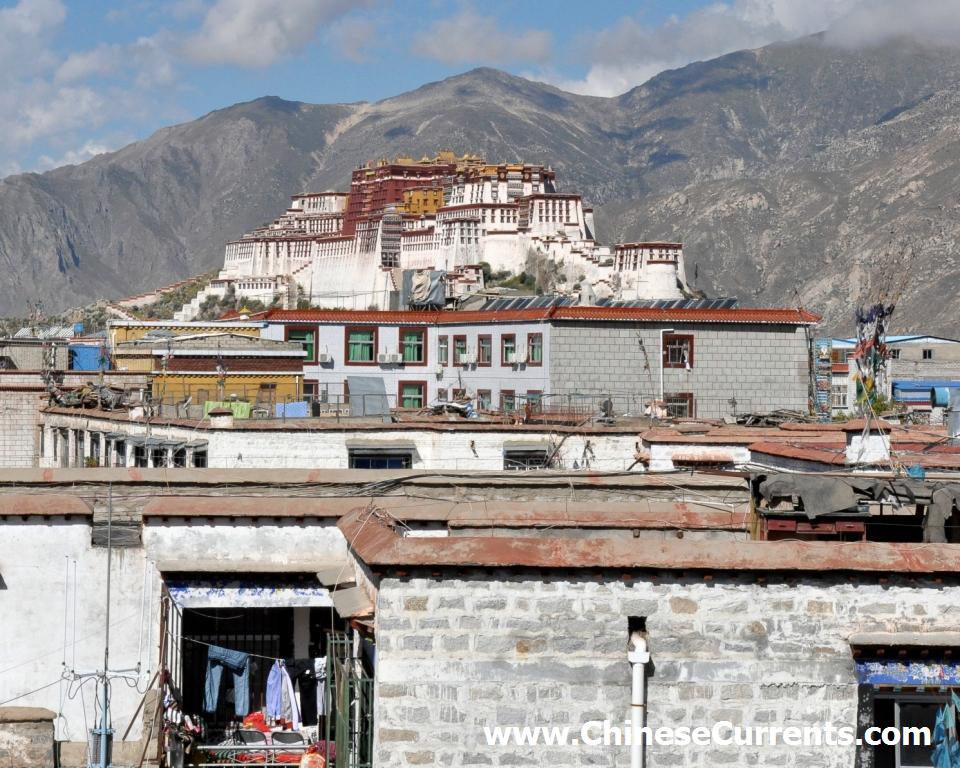

"Seven days in Lhasa",

Tibet 27th September to 3rd October 2010

"Lenovo headquarters",

Zhongguancun, Beijing Wednesday, 15th September 2010

"Shopping break",

Ikea, Chaoyang, Beijing Saturday, 11th September 2010

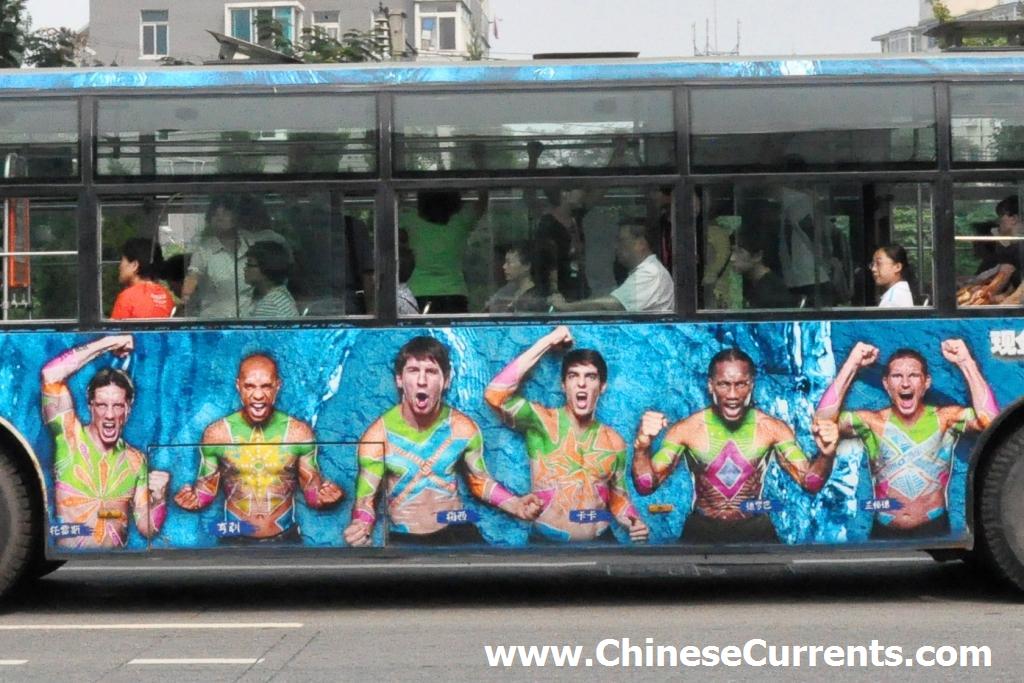

"Symbolism", Beijing Friday, 10th September 2010

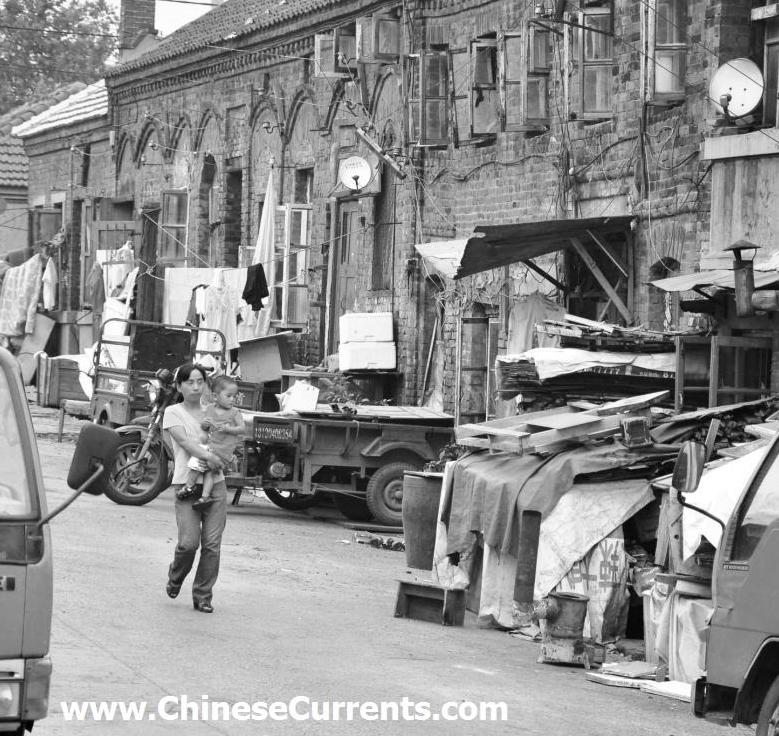

"Out and about",

Chaoyang, Beijing Wednesday, 8th September 2010

"Out and about", Nanjing, Jiangsu province Monday, 30th August, 2010

"Out and about", Guangzhou, Guangdong Sunday, 29th August, 2010

"Out and about", Xiamen, Fujian province Saturday, 28th August, 2010

"You pick it, we'll cook it",

Xiamen, Fujian Friday, 27th August, 2010

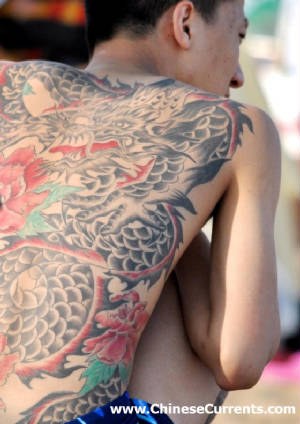

"Fun for all the family",

Shantou, Guangdong Thursday, 26th August, 2010

"Coasting it", Shenzhen to Shantou, Guangdong Thursday, 26th August, 2010

"Open for 30 years", Shenzhen, Guangdong Wednesday, 25th August, 2010

"Gucci poster", Beijing

airport Wednesday, 25th August, 2010

"White Knuckle Ride", Beijing, Chaoyang Park Sunday, 22nd August, 2010

"Love, Love, Love", Beijing, central railway station Saturday, 14th August, 2010

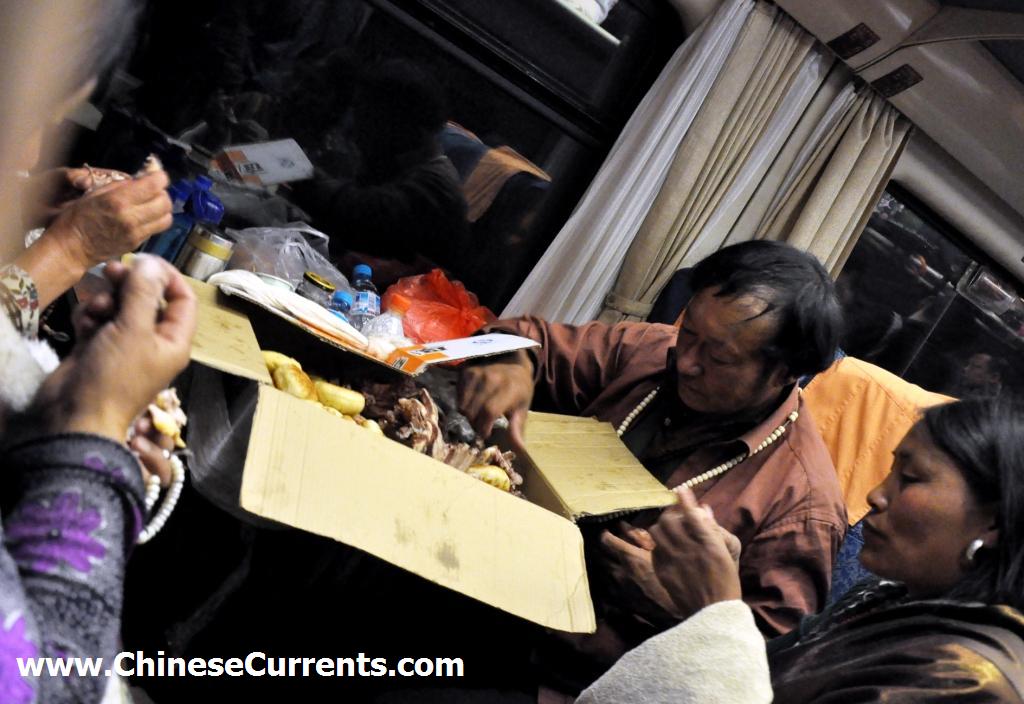

"Long Ride Home",

Beijing, Shunyi Thursday, 12th August, 2010

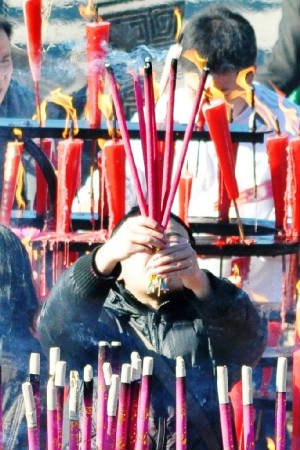

"A Prayer for the New Year",

Sichuan, Emei Shan

"Dawn on New Year's Day", 2010;

Sichuan province, Emei Shan

Spinning the wheel Thursday,

23rd December 2010; Beijing

|

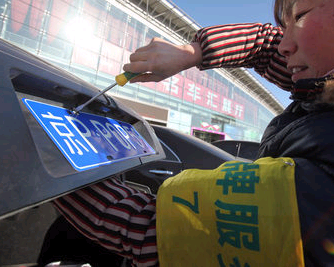

| The lucky ones |

Roll

up! Roll up! Hang on a minute… the odds are that people in this particular lottery won’t be

rolling anywhere anytime soon. The capital city of the nation that outlaws gambling (with the exceptions

of state and provincial-run lotteries of course, not to mention the rollercoaster stock exchanges) announced today that it

will introduce a lottery for car registrations from January 1st.

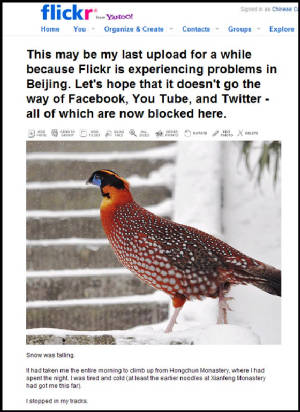

But blogs and forum bulletin

boards all over China have been buzzing with news of the impending legislation for at least two weeks. The

question on many people’s lips is, which city will be next (and when)?

Another hot question is,

what’s the point of denying people the right to buy a car when there are other – far more effective ways –

of reducing traffic congestion? The reality of course is that the measure has not been designed to

reduce snarl ups. That was never the aim. The people behind the scheme have a far more

modest ambition: to slow down the rate of growth of future registrations.

At the end of 2010, the number of Beijing-registered vehicles is likely to hit the five million mark; 900,000 of which

would have their ‘jing’ number plates registered this year (‘jing’ is the character

on the plate that signifies Beijing registration).

Next year’s cap has

been set at a ‘mere’ 20,000 vehicles per month (240,000 vehicles in total) – perhaps about a quarter of

2011’s potential demand. That doesn’t seem a lot, bearing in mind that 30,000 vehicles were

sold last week alone as panic buying spread all over the city after word of the impending legislation got out.

Which brings me to the

blow that will be dealt to the economy generally and the auto-industry in particular: The economic ‘loss’

of about 750,000 car sales is significant. Just as significant is the effect on the psychology of the business

planning of the auto-companies – if Beijing can install such a drastic measure with only a few days ‘official’

notice, then what’s to stop a dozen cities or more changing the rules at a moment’s notice.

The long supply chain of

car manufacturing necessitates that production is geared-up and geared-down slowly and smoothly, and that the expenditure

levels of marketing activity is set months ahead of the planned-for sales shift. Auto-companies plan years

and quarters ahead, not weeks and days. So, if the policy is suddenly rolled out to other cities, the rapid

turning of the auto-production supply tap from full-flow to a trickle will have severe consequences.

If, on the other hand, the policy

is not rolled out beyond Beijing, then the auto-makers’ suffering (and the suffering of the economy that relies on them)

will be manageable – although the companies who sell proportionately more volume in Beijing will of course be worse

off than their competitors whose sales are not so reliant on customers in the capital. That said, if you

were the boss of an auto-company, would your China 2011 (excluding Beijing) plan be bullish, or would you gear-down production

just in case? If you were the owner of a car dealership in Beijing, however, the future is less uncertain

– it is unquestionably bleak.

If other cities don’t

follow suit – and I believe they would be ill-advised to do so – then one of the Beijing government’s most

unpopular policies in recent times will become even more unpopular. Watching people in the comfort of their

cars drive past you as you stand at a bus stop or wait for a taxi on a frigidly cold Beijing night is one thing, but –

for would-be car owners who haven’t won the number plate lottery – the feeling of injustice would be compounded

if Beijing were the only city to treat its citizens in this way.

Ms Jin is one of the millions

who are upset by the new legislation. She writes on her blog, “I started working three years ago

after leaving university, and have been saving up for one ever since. I was hoping to buy a car next year,

but now I realise I have to try my luck in the lottery. I’ve never won anything in my life, so I

don’t hold out much hope. It’s so unfair.”

What Ms Jin doesn’t realise,

however, is that she won’t even be allowed to enter the lottery. According to her blog, she is from

Xi’an, and will therefore have a Xi’an hukou (registration document). She is what

is termed a waidi (an outsider) and as such she will be barred from registering a vehicle in Beijing from January

1st. It makes no difference that she studied in Beijing for four years and has lived in Beijing a further

three years.

This new vehicle legislation

is just the latest example of discrimination against the millions of waidi in the capital, who are denied the privileges that

many people with a Beijing hukou take for granted.

The damning criticism of

the policy thus far from Beijingers and from the waidi who have worked out that they are to be

barred from entering the lottery – has already caused one high profile head to roll. When harmony

has been so disrupted; someone – whose position is high enough to send a signal to others, but not so high as to upset

the order of things – must be blamed and publicly humiliated.

So, spare a thought for

Huang Wei, a former vice mayor of Beijing municipality, who has been unceremoniously transferred from

Beijing to the north-west-frontier region of Xinjiang – more than 4,000km from the capital. Assuming he is driven there and that he

gets to keep his Beijing-registered car, then at least that will be one car fewer to clutter Beijing’s roads.

There will also be one car fewer with a municipal-government licence plate (700,000 of which are reported to be on

Beijing’s road) to upset the people in the long queues for a Beijing bus or taxi.

|

| The "Jing" cherished plate |

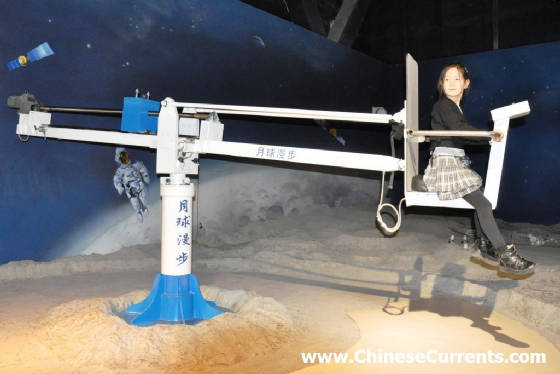

Strolling on the Moon Saturday, 27th

November 2010; Beijing

|

| "...inspire innovations ...": The sign's call to action |

If you happen to be in Beijing with a seven year-old

and you think that it's too cold/hot/windy/polluted to visit the zoo, the Fragrant Hills, or one of the many public parks

(as it tends to be most weekends of the year), then you could do much worse than to head for the Science and Technology Museum

(just east of the "Bird's Nest" National Stadium). From a distance, the cavernous structure that houses

the museum looks like it has been built by a giant child using toy bricks. Then again, there may be those

who prefer the description on the official website: "The embodiment of the intrinsic correlations between man

and nature as well as science and technology." Keen

to find out more about these "intrinsic correlations" (and also to escape the painfully cold north wind) I

paid the 80 yuan admission price for the two of us, and hurried inside. My first impression was that

I had entered the same giant-child's play room: a dizzying combination of space and scattered games

and activities. The action was on five levels, each with its own theme and vibe: The "Children's Science Paradise"

section was the first port of call. Then we moved on to "Exploration and Discovery", "Science,

Technology and Life", "Innovation and Harmony" and last but by no means least, "The Glory of China". Wherever we went, there were lots of things for the eager hands

and inquisitive mind of a seven year-old to explore. As interesting as my daughter found the exhibits, I couldn't

help thinking that it was all a bit tame and rather pedestrian. Perhaps I've spent too much time watching The Frizz...

the red-haired, high-spirited science teacher who drives The Magic School Bus. In every episode she implores

her students to, "Take chances; Make mistakes" before venturing out to explore an exciting aspect

of science. "Chances" and "Mistakes", however, seem to have no place in the Beijing Science

and Technology museum, which presumably sticks tightly to the guidelines dictated by China's school-curriculum. All of the activities on offer had predictable and certain

results. Take "The Amazing Journey of a Ball", one of the showcase exhibits, for example. If you know

about the Mouse Trap game, then imagine a giant roller-coaster version. Or think about the Honda precision-engineering

TV commercial... the one that demonstrates a chain reaction of car bits falling, ricocheting, and

colliding... that eventually trigger the windscreen wipers. In the Science and Technology museum version,

kids are encouraged to set ball after ball in motion from different heights (select height A, B, or C); use compressed

air to start stage 2 of the quest (one setting); and then propel the balls onwards and downwards (select force A,

B, or C) to complete the circular journey. Balls fly through the air, bounce off angled metal discs, land in wire

baskets, swoop down chutes... all in a mesmerising blur. But there wasn't a single ball that failed to make it

round the circuit because a child had applied too little or too much force or taken too long or not long enough to pull a

lever or press a button. Then there

was the "moon-walking" experience. There was a 20 minute queue of excited youngsters waiting

to take their turn. But, hey, what's a 20 minute wait when you can come away thinking that you have walked

in the footsteps of Neil Armstrong. I remember the grainy, ethereal footage of Armstrong's moon-walking in 1969,

when I was about the same age as my daughter. I watched open-mouthed at Armstrong's antics as he performed the

highest of high-wire circus acts that was a quantum leap beyond moon-walking. It was full-on, no-holds-barred moon-leaping,

or moon bunny-jumping, or moon-bouncing, or perhaps even moon-bounding. He looked like a man that had taken his

"giant leap" speech to heart. He bounced for joy because he was thrilled to be there.

Boring-old "moon-walking" (NASA's preferred term), was presumably designed by PR gurus to make it appear less

dangerous than it clearly was. Cut to Beijing,

2010. Each kid is weighed before being allowed to take her or his "maximum two minutes" turn on

the contraption that is pictured below. The weight of the child determines how far the counter-balancing weight is

moved back. Thus, each child gets the same degree of movement. But, no matter how hard

you try to change the laws of physics (and goodness knows my daughter tried really hard) all you can do

is move, very slowly, up a little, down a little, and sideways a bit. No bouncing/leaping/bunny-hopping/bounding allowed

apparently. What is wrong with a "gravity joy-stick" to control your own elevation and bounciness for goodness

sake. I then noticed the Chinese characters stencilled on the side of the machine: "moon-stroller" (obviously

designed with harmony in mind). Talking

of harmony: The stated theme of the Science and Technology museum and the official translation of the yellow Chinese

characters you see in the above photo is (I'm not making this up by the way): "To experience science and inspire

innovations; to serve the general public and promote harmony". It seems that every public building, every

newsworthy project, every public statement, and every domestic policy that's written about in the China press (or

appears as an official slogan) is designed to "promote harmony". Which is all well and good of course.

Particularly when it is the result of innovation that has been inspired by a visit to the Science and Technology

museum. I am sure that the vast majority

of the thousands of kids who visited today would have been genuinely excited by some of the things they saw. I can't

help thinking though that they would have been even more inspired had they been challenged to "Take chances"

and "Make mistakes". On the contrary,

the Chinese education system instils the opposite philosophy into its teachers and students. In the highly-competitive race

to pass the gaokao (or college and university entrance exam) students will be made to learn several

hundred "standard answers" by rote. Neither the teacher nor student (both of whose career progression

depend on getting high scores) will stray from carefully rehearsed responses to set questions. The torture begins

from an early age, because only the highest-scoring primary school kids can get into the best-scoring middle schools whose

intake have the best chance of progressing to the best-scoring high-schools... which are, in turn, likely to groom the

best gaokao scorers. It's not surprising, then, that in a survey covering 21 countries, conducted by International

Educational Progress Evaluation Organization, Chinese students finished (joint) bottom of the class in terms of their

ability to use their imagination. Nor is it a surprise that Chinese kids were top of the class in maths. The China Daily, in a hard-hitting (for them) editorial

said yesterday that "This global study should make us swing into action and help our students to throw open their young

minds to imagination and creativity". The article goes on to say that it is the parents' as well as the educators'

responsibility to make kids use their imagination. While I agree with this, I can't help feeling that it is the system

that sets the agenda. Chinese parents feel that they have no choice but to focus their energy and hard-earned income on helping

to improve their child's exam score. Inevitably, the development of their child's imagination suffers as a

consequence. Parents know that the kids who

get to the best universities –

by dint of them achieving high gaokao scores – are likely to get on the fast-track to the best careers

(in the fields of technology, government administration and business). Many parents

are not aware, however, that the really high-achievers in the exam – the gaokao zhuangyuan (the top scorers, the ones that didn't

make mistakes) –

are actually the serial under-achievers... Earlier this year, the China Daily reported that, "A survey that kept

track of more than 1,000 top scorers from 1977 to 2008 found that none of the top [scorers] stood

out in the field of academics, business or politics." So there you have it... proof – if proof were indeed needed – that those who

never made a mistake never made anything.

|

| Strolling on the Moon at ..click image to visit the Science and Technology website |

Dave pops into Tesco Tuesday, 9th

November 2010; Beijing

|

| Dave Cameron in Beijing today (photos from Tesco's China website: click on image to view) |

If you find yourself in Beijing with just 48 hours to take in the sights

you've been dreaming of visiting ever since you discovered China in Boy's Own, then where to go? The Great Wall? According to a Chinese proverb you can't call yourself a man until you've been

there, so how could you not. Tiananmen? A must. Peking University? Big tick. The Great Hall

of the People? Rude not to if your hosts are throwing a banquet in your honour. Tesco? First port of

call of course. Dave was so eager to browse the aisles, in fact, that he was driven directly from the airport to the "Happy

Valley" store in Chaoyang district. Not surprisingly, Lucy

Neville-Rolfe, Tesco’s Executive Director of Corporate and Legal Affairs, who is one of the trade delegates to accompany

Dave was "...absolutely thrilled to welcome the Prime Minister to Tesco in China”. It wouldn't have taken Dave long to realise, though, that not many of the products on the

shelves were "made in Britain". Some products would have been more conspicuous by their absence than others.

I wonder if he had –

as I have done more than a few times –

searched for Walkers' cheese & onion crisps only to discover that the only premium brand of crisps on sale is Lays...

a fine crisp of course, but not in the same league as good old Walkers' C&E. Unfortunately for British exporters, the store's 40,000 customers per week don't go there looking

for the "Best of British", such as Norfolk's Binham Blue (which, by the way, is the best cheese in the world...

in my view at least). The reason they go there of course is that Tesco has built its success in China on giving people

what they know and like at hard-to-better prices. So successful has Tesco become that they

now employ more than 23 thousand people on the Chinese mainland, and are within weeks away of opening their 100th store here.

Not a bad achievement considering they opened their first store just 6 years ago. And, according to Ms

Neville-Rolfe, "..There’s plenty more to come": US$3 billion more over the next five years according

to news reports. The company clearly has its sights set on closing the gap between

itself and Carrefour, whose 2009 sales (according to Euromonitor, a research company) reached 33 billion RMB... three times

that of the British late-comer, but still a long way behind the 45 billion RMB amassed by Walmart, the number one

international brand in the category, which opened its first shop on the mainland in 1996 (click here to view Walmart's Chinese website). Increasingly, though, the revenue that Tesco accumulates from

its 4.5 million weekly transactions (versus, btw, 20 million in the UK, where it is number one), although impressive,

understates its achievements here. That's because the company has begun to invest heavily in "lifespace

malls". The first one of which opened in Qingdao, in Shandong province, in January, with reportedly 50,000 people

flocking to the opening event. Tesco operates a store within these malls and rents the rest of the space to cinemas,

restaurants and other retailers. The biggest Tesco "lifespace mall" was opened in Qinhuangdao

in Hebei province in February. Bloomberg reported in September that this "400,000-square foot (37,161

square-meter) mall... attracted a quarter of million visitors" since it opened and, like me, couldn't resist

adding that the "store [within the mall] features grocery products displayed with a 'market' atmosphere as employees

call out the price of live crabs in ice buckets..." The next time I'm in Qinhuangdao I'll make sure I take

in the vibe, as well as reporting back to you what the Tesco crabs are like. Talking

of crabs, I wonder if someone at the British embassy has taken the fast train (under two hours) to Qinhuangdao to buy several buckets-full

for the embassy bash in honour of Dave and his entourage (4 ministers, several academics, and more than 40 captains of

industry –

the largest British trade delegation to visit China for centuries apparently). No doubt that

the Qinhuangdao Bo Sea crabs – reputed

to be among the sweetest in China –

will taste even sweeter after word gets round that they have come from Tesco.

|

| Tesco's Chinese website (Click on the image to have a look at it) |

Changing tides Tuesday,

19th October; Shenzhen, Guangdong province

|

| Luxury SUV car of the year... 2006 and 2007 |

Did you know that the Beijing-Shenzhen-Beijing round-trip

is 2,416 air miles – which is actually one dozen miles further than the distance a London-based crow would have to fly

to check out the delights of Timbuktu? So, what’s the point of this somewhat laboured – not to mention gratuitous – analogy, you may well be wondering (assuming you have got this far to wonder it). I am, for the benefit of those who haven’t suffered it, simply trying

to paint a picture of just how extreme an undertaking a day trip from Beijing to Shenzhen really is. I hit the big 50 a few days ago and, on the flight back, as my watched ticked on

past midnight, I can honestly say that I was feeling every day of my age. The 30 minute wait for a taxi

at 2am in the morning at Beijing’s showcase terminal three, did nothing to improve my well-being score. But, although the day

was exhausting, there had been a number of comforting positives. As I waited for my nocturnal taxi in one

of Beijing’s more disorderly queues, I reflected that the day could have been much, much worse: I had arrived at Shenzhen

airport at 11.30 that morning. The driver, who had been kindly sent by the company who had invited me to

Shenzhen to speak at at their global marketing conference, was there to meet me at the gate. We shook hands. “Where’s your luggage?”

he asked. “I only have my computer and camera,” I explained. “But

you’ve come from Beijing… won’t you be staying the night?” I told him that I was

booked on the last flight back, and that I would have to make a sharp exit from the conference hall as soon as I had finished

my bit. Mr Wei laughed, “It’s a long flight to Beijing, you’ll be tired”. I followed Mr Wei to the car park. I saw it when I turned the corner. No! It couldn’t be... ...We were walking straight

to it and there was nothing else in sight. How would I be able to live this down? Generally, I really don’t mind what car I ride in. I say

generally, because there are a few exceptions. On top of the small list of cars I would prefer

not to be seen in – let alone pull into the headquarters of a major corporation in – is the Porche Cayenne. I have disliked the car – if it really is a car – since I first saw

it in China (there were two of them, in fact, parked outside neighbouring houses in one of Shanghai’s swankiest parts

of town).

Don’t get me wrong, I do quite like

Porsches – proper ones that is, the ones that look, sound, and handle like sports cars. But, this

thing? What were they thinking? Jeremy Clarkson, the writer and presenter on Britain’s number

one (in fact, only) series about cars and driving, Top Gear, was so under-impressed with its looks that he was moved to say,

“Honestly, I have seen more attractive

gangrenous wounds than this. It has the sex appeal of a camel with gingivitis.” Mr Clarkson then

went on, in his Sunday Times column, to describe it as the the car that had drowned in “Lake Ugly”. Okay, I know it’s been successful – particularly so in China,

where the majority of Porsches sold are Cayennes – but that doesn’t make it any less… now what word would

I pick…. yes, any less crass. Crassus, the latin parent of the word, adds that bit more to the description:

thick, dense, fat, heavy. Students of Roman history (as well as those, like me, who bothered to look him

up in Wikipedia) will know that Marcus

Licinius Crassus was the wealthiest man in the Empire. He impressed people (most famously, Julius Ceasar)

with his colossal political 'donations', but not with his taste. Crassus was wealthier

than any mortal being, but his lack of refinement and sophistication made him, well, a bit of a laughing

stock among those who knew a priceless Roman urn from a cheap Greek one. Taste in luxury products among those who can afford them has moved on a

lot since 2005, when “unskilled rich” property tychoons were known to travel from Shenzhen to Hong Kong to buy

the most expensive items in the shops – without knowing anything much about the brands they were buying.

Vertu, the draw-droppingly expensive, and some would say ridiculous-looking diamond-studded mobile phone, was

(and for some still is) high up on the list of luxuries to carry back to Shenzhen. In 2006, the first year that the Luxury SUV (sports utility vehicle) category was included in the Hurun survey

of the “best of the best” (luxury brands), the Porsche Cayenne claimed top spot. The people

from Porsche were invited to deliver another acceptance speech the following year for the same range of vehicles.

However, in 2008, the

tide turned. The luxury-category influencers who were surveyed by Hurun, voted instead for the BMW X, which

also carried off the title in 2009. In 2010, it was the Audi Q7 that won the respondents’ vote.

Cayenne sales have continued to increase year after year, but in recent years the rise has as not

been as fast as category sales. The important driver, if you’ll forgive the pun, is that

the Audi Q7 stands for “new wealth” and “new ideas about how to enjoy your wealth”, which has struck

a chord with the New Wave of China’s rich (and also those among the waves gone by who are keen to go with the flow

of the changing tide). The New Wave (the biggest, most powerful wave yet) prefer the refinement

and understatement of the Audi Q7 to the in-yer-face brooding presence of the Porsche Cayenne. The extent

of the swing, instigated by the influencers – those on the crest of the New Wave – is such that full-year 2010

sales of the Q7 are likely to exceed that of the Cayenne. Back in the car park, I stared at the grotesque

Cayenne and resignedly shook my head. But, just as I was working

out how to explain my hypocrisy to my friends, Mr Wei ran ahead of me and seemed to disappear behind the Cayenne, from where

I heard a door being manually unlocked. I was delighted to discover that, hidden behind the Cayenne, was a white

van. And it was not just any white van… it was a mianbao che ['bread van'] no less. A

'bread van' my not be my first choice of chauffeur-driven transportation. But, given a choice of it, a

Beijing taxi, an Audi Q7, or a Porsche Cayenne, the bread van would certainly be my second-pick every time.

And, in case you are wondering,

the Beijing taxi would take third spot... even if I had to wait 30 minutes for it at two in the morning.

|

| Diamond-studded luxury in Shenzhen |

Tale of two taxis 27th

September to 3rd October 2010; Lhasa, Tibet

|

| One of the red-flagged Lhasa taxis |

I

arrived at the hotel reception at about 6pm. I was exhausted, but still very much on the kind of high you can only get

from traversing one of the most incredible regions on the planet Earth. The receptionist looked pleased to see me. Until, that is, she realised I didn't have a Tibet entry

permit. "Don't have one?!" she said, with the wide-eyed look of someone who'd just had a premonition

that a tall stranger from a far away land would be a bringer of trouble and strife. "No, I don't have one,"

I repeated. "This is my third visit to Lhasa, and my fifth visit to Tibet and this is the first time anyone's

asked to see a Tibet entry permit." "But you must have one to be here!" She was beginning

to raise her voice, so I thought it would be better to employ ice-cool calmness: "It can't be true

that I must have one to be here because I am here and I don't have one..." I was beginning to sound as well

as feel like Alice following her arrival in Wonderland (same rude welcome, but at least she only had to fall down

a rabbit hole to get there). However, despite my good intention to hold it together, my sleep-deprived mind wasn't

in calm mode and I could feel my composure ebbing away with every word of my explanation: "... I can

show you my passport, my visa, my Chinese driving licence, and my Beijing to Lhasa train ticket – which, I might add,

was checked numerous times by numerous people on the train, and was even checked by two policeman before I crossed into Tibet.

Two policeman who said absolutely nothing to me about needing a permit to be here. "I can show you all of those things, but I cannot show you a

Tibet entry permit, because I DON"T HAVE ONE. I have absolutely no desire to be here if I am not wanted here,

so..." I the realised that I had said the "so" without knowing what the "so" was, so I prolonged

the the "oooo" long enough to think of a suitably dramatic punch line. "...does this

mean I need to sleep in the street and get the morning train back to Beijing?". She tilted her head to

one side and then to the other, as if sizing up the situation, before telling me that she needed to call her

boss. I awoke not knowing where I was – the memories of the past three days swirling around

in a bewildering montage. I then heard the yapping dogs that had kept me awake half the night, which I

found strangely reassuring because the sound at least reminded me that I was in a hotel room in Lhasa. I

then remembered that today was the day I would return to the mountain nunnery I had visited in January 2008. That

time, it had taken a helpful concierge ten minutes to find a driver who knew the way. This time it would

take 15 minutes. The same receptionist who had eventually given me my room key after her boss had confirmed

I could stay, kindly offered to find the "right" taxi for me, because “Only a few drivers know how to get

there”. I asked her how she knew which drivers would know the way. “Only

locals know the way there,” she said matter-of-factly. “And how do you spot a local driver,”

I enquired. “Oh, you can just tell,” she responded dismissively. Most

of the taxis were full. But then an “empty” taxi – a shiny new Brilliance (made in Shenyang)

– slowed down, the driver not unreasonably thinking that we wanted to hire him. The receptionist

waved him away. Clearly, not the “right” one, I thought. Several more “empty”

Brilliance taxis were allowed to pass by, before the receptionist spotted one that she thought would be able to take me to

the mountain-nunnery. A battered old VW taxi was flagged down. My helper spoke to the

driver in Tibetan, before confirming to me that this driver would indeed take me where I wanted to go (2 hours away from Lhasa),

wait for 4 hours, and return to Lhasa – all for a price I thought was reasonable. Thanking

the receptionist for her trouble, I climbed in to the front passenger seat. This could have been – I would

later realise – a fatal mistake. The driver, an early-thirty-something, sporting a Kappa tracksuit

top, nodded a hello. It didn’t take me long to work out that this was a driver in a hurry.

Before I had shut the door, he started to perform a G-force inducing U-turn. This

set the mood for the rest of the nail-biting journey. I deduced that – let’s call him Mr T

– had a worryingly high level of speedosterone, a chemical that seems to affect more than a few thirty-somethings the

world over. The reality was he was driving a battered VW, but that didn’t stop Mr T driving on and

sometimes beyond the limit. Everything that was ahead of us didn’t stay ahead of us for very long.

That was until we encountered a Toyota Landcruiser. Mr T raced up behind it, slammed the gearbox

into third and, with the engine shrieking its protest, was just about to execute an overtaking manoeuvre on a blind bend that

would have been logged by accident investigators as “travelling at least 30km over the speed limit”, when I screamed

out: “Wu Jin!!” Mr T hadn’t noticed the WJ number plate (he had been too busy

reciting a Buddhist sutra as he passed a prayer-flag bedecked shrine, while talking on his mobile phone to one of his mates).

The WJ signified that the car in front was not just any Toyota, it was a Toyota carrying Wu Jin – an

armed-police response unit. “Oops,” said Mr T, as he lifted off the accelerator, “I didn’t

spot that one”.

|

| CLICK ON THE PHOTO TO SEE MANY FAR MORE ROMANTIC PHOTOS OF LHASA AND TIBET |

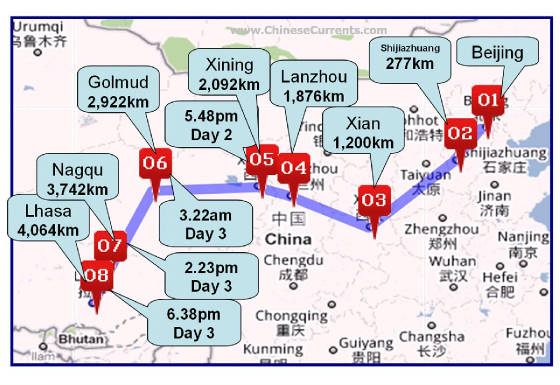

Ticket to ride... on tonight's Sky Train Saturday, 25h September 2010; Beijing

|

| Ticket to ride... the hard way |

"You're going where?!" asked a friend. "Lhasa," I repeated. "How long does the flight take?" he asked.

"I don't know, I'm taking the train," I replied. After I had gone on to tell him that

I would be sitting on a "hard seat" for more than 45 hours, he wished me luck. Not that I wouldn't prefer a bed of course, but all the "sleeper" tickets had

already been sold by the time I got around to deciding that I would return to Tibet. On the plus side (and I am

sure you can understand why I think it's an incredibly small 'plus'), the "hard seat" for the close-to 2,500

mile train journey costs only 389 yuan (or the equivalent of about US$58 or 37 pounds sterling). The last time I travelled there, I took the same

"Sky Train", the T27, which departed from Beijing West Railway Station at 9.30pm on New Year's Day,

2008. Then, I had been lucky enough to get a "hard sleeper" ticket – my preferred style of travel during my 35-day 10,603 mile

(about 17 thousand km) rail journey around China (click here if you would like to see where else I went). The 4,096km ride was so exhilarating that I swore to do the same trip

again one day. As well as offering a wonderful opportunity to listen to dozens of people talk about themselves and about

their reason for making the arduous trip, the backdrop to these conversations is simply awe-inspiring:

The shift in altitude from Beijing West railway station at about 35 metres above sea level (masl) to the end of the line at

Lhasa station at 3641 masl (just short of 12,000 feet) is ear-popping enough, but it is the final two sections between

Golmud, station "number 6", and Lhasa that are most dizzying. 80 per cent of the track from Golmud

to Lhasa is at more than 4,000 masl, including 550km of which has been sunk into permafrost. The beauty of the early-evening

arrival time into Lhasa is that you can spend the entire "Day 3" of the journey enjoying eye-poppingly wonderful

vistas. The highest point of the

journey (indeed, the highest point of any rail journey in the world) is reached a couple of hours before Nagqu, station "number

7". The height on the altimeter to watch out for is 5,072 masl (16,640 feet), which signals that you

have reached the Tanggalu Pass, the boundary marker of Qinghai and the Tibet Autonomous Region.

From here, it's downhill (about a vertical mile) to Lhasa.

All of this assumes, of course, that I am allowed to cross into Tibet. Most websites that profess to

be experts on tourism into the area tell you that you will not be allowed in without a special travel

permit (the process for getting one is a long and uncertain one I understand). On my last attempt, I managed

to get all the way there and back without one (the hefty price of which includes, by the way, an "official guide").

No one is quite sure if there has been a tightening of the unwritten rules since my last visit... Well,

there's only one way to find out...

|

| The 8 Sky Train stations, arrival times, and distances from Beijing |

Apple blossoms in China Friday, 17th

September 2010; Sanlitun, Beijing

It rained heavily all day today in Beijing. The first cold front of the autumn had

also blown in air that was 14 degrees centigrade cooler than the highs of recent days. But the inclement

weather mattered not a jot to the crowds who flocked to the Apple store in Sanlitun Village. Hundreds had

waited in the pouring rain for the 8am opening – that

signalled the long-awaited launch of iPad in China (Apple's other shops in China would open at 10am). The first in the queue was Han Ziwen, a bookshop owner,

who had – according

to a shop assistant I spoke with – been

queuing since Tuesday. Photos of him, proudly wearing his "I BUY IPAD NO1" shirt, and holding

aloft his brace of iPads (the most that one person is allowed to purchase at any one time) are already all over the Internet. It seemed that – like the beaming Mr Han – everyone leaving the shop with an iPad was struggling to contain

their excitement. "Which one did you buy?" I asked a man in his mid 30s, who was doing his best, but

failing badly to contain a cat that got the cream look. "64!" He said with a grin that was as wide as a well-fed

Cheshire cat's. The 64GB is the top of the range model that is selling for 5,588 yuan (about US$825). "How

does it feel to have one?" I asked. Words, it seemed, were not enough to express his excitement. Instead,

he punched the air jubilantly. With that, I went inside and waited for one of the many demos to become available.

After 15 minutes, my turn came. My first port of call was the ebook application. There were two pre-loaded

books to choose from. I chose Winnie the Pooh – a

favourite of mine. I had never flicked through an ebook before (as in turning the pages with one's

fingers), and at once I realised that the pundits who are forecasting a serious decline in the sales of physical books

are likely to be proved right. Suddenly, Tigger – whom you may remember is "bouncy,

trouncy, flouncy, pouncy", and "Fun, fun, fun, FUN" – pounced

off the page and appeared in front of me. "Hi!

Can I help!?" pleaded an eager-faced Chong, an Apple 'helper' (I can't bring myself to call him a salesperson,

because it never felt like he was trying to sell me anything). I thought for a moment before asking him to show me how

to use the Wi-Fi. In two shakes of a Tigger's tail, I was connected to my requested site. He then told me all

about the nifty device that for 80 yuan a month would keep me connected to the internet anywhere in China (rendering redundant

any concerns about the China iPads lack of 3G compatibility). I was struck by Chong's incredible energy and unadulterated

love of what he was doing. He then

spotted I had a camera with me. "Hey!" he said, "The iPad is great for photographers!

He then explained how the card reader that's compatible with the iPad ("you can buy one upstairs") could enable

me to travel light on my journeys around China. I thanked him for the advice, and he bounced away with a cheery, "Shout me

over if you need any more help!". No sooner

had I got back to the iPad, Chong bounded back to my side. "Hey!" he said, "I've

just thought of something you'll really like!" He then picked up the iPad, and pressed a Google

Earth button that pinpointed the Apple store in Sanlitun (homing in on the Wi-Fi signal I guessed). "Now,

wait for this," he said, with the aplomb of a conjurer who was supremely confident of his ability

to pull a rabbit out of his hat. "Enable compass!" he said theatrically as he pressed

something on the iPad. "And away you go!" The map on the iPad was then showing me that it was pointed

in the direction of Gongti Bei Lu, due south of the shop. I have this facility on my mobile device, but I must

admit that it is far more digestible in tablet form. "How

long have you been doing this job?" I asked. "One year," he replied. "Before that

I was in the education business in Guangzhou, but I just had to come to Beijing to work with Apple." Chong

was on a roll: "I LOVE it!" he exuded. "I LOVE introducing people to new things,

and showing them how simple it is to get more from technology. Apple is so simple to use," he continued,

"Anyone can benefit from using it." I was dumbfounded. I had worked with Nokia in China for 5 years,

and it was as if the Nokia "human technology" mantra had been given a new lease of life. I thanked

Chong again, who shook my hand again before bouncing over to one of the other demo tables. With people of his calibre;

with such a pleasurable browsing experience; and with technology this cool – there is no doubt that the brand will go from strength to strength in China.

What's more, Apple's long-standing barrier for many – pricing –

(which has always been the brand's double-edged sword) is much less of an obstacle than it was before

8am this morning. I stepped back from the table, gesturing to the mid-twenty

something woman – who was

standing over my shoulder sensing that I was about to move away from the table – to take my place. "Thanks!" she said. After a few

minutes chatting I realised that the iPad really is a game-changer for Apple in China: Ms Wang sums up the magnitude of the shift that Apple has pulled off:

"I never thought I'd be able to buy an Apple computer, but I now realise I can buy their very latest model for under

4,000 yuan!!" I bet, though, that when Ms Wang (and millions more like her) has played for 30 minutes on the

iPad, and had a chat with Chong or one of his colleagues about her options, the 1,600 yuan more that's required to buy the

64GB model (versus the 16GB) will –

all of a sudden – seem to

be quite a small price to pay. [You are welcome to click HERE to view my in-store photos from today's visit.]

|

| The Apple of their i |

The number 1 "Chinese Brand City" is... Thursday, 2nd September 2010; Dalian, Liaoning

|

| Dalian... One of China's most upbeat cities |

I looked at

the headline again. What do they mean by “Chinese Brand City” I asked myself?

Has Dalian been awarded the title of the number one city brand in China, or is Dalian the number one city for Chinese

brands? The answer, according to the 12th August China

Daily article, written by Guo Changdong and Ren Ruqin, is the former – Dalian has won the accolade of number one

city brand in China.

The article states: “The committee [made up of representatives

from the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade and the Brand China Industry Union] praised Dalian’s

efforts in promoting itself and building a culture with romantic and trendy characteristics. Dalian has done much work in

industrial restructuring, and forming a liveable city environment. The rapid economic development helps Dalian to build its

brand image.”

Well there’s a lucky bounce, I thought to myself, as

Dalian is my final port of call on a nine day tour that has included six Chinese cities. A great opportunity,

then, to compare and contrast Dalian’s development with that of Shenzhen, Shantou, Xiamen, Guangzhou, and Nanjing (from

where I had flown). As well as the 6-city development differences I am also keen to see if I can spot any

changes since my last visit here in 2007. My first impressions, I have to say, were not positive.

Maybe I am staying in the ‘wrong’ part of town

this time – in the far east of Zhongshan Road, the main thoroughfare that dissects the older part of the city.

Or maybe it was a bad day in terms of pollution or humidity. Or perhaps I was suffering from travel

fatigue. Whatever it was, my three mile walk down the entire length of Zhongshan Road left me thinking

that central Dalian was looking… well… more than a little tired.

However, GDP per capita (73,134 yuan) and urban income per capita figures (19,090 yuan) in 2009

all show very healthy year-on-year gains. And all other key economic indicators show similarly robust growth.

As I was puzzling over the conundrum, I remembered that I had spent the bulk of my time on my last visit away from

the central area. In 2007, I had toured the Dalian Development Area (DDA) – the shiny part of town

as well as Dalian’s engine for economic growth. The DDA is so important to China’s economic

development that it is controlled by China’s state council in Beijing, not by Liaoning’s provincial government.

So, could it be that my impression of Dalian in 2007 had been

skewed by a number of positive experiences (which included interviewing a Ferrari salesperson, who was the personification

of Dalian’s reputation of a “nothing is impossible” pioneering city... click here to read the article) and that my observations this time could not and should not be compared with my 2007 impressions? I went to a bar to find out what the locals think: Mr Cao, the bar owner, had no idea about Dalian’s “best city” award.

He also had quite a negative view of Dalian’s current economic position. “Things have

not been great since Bo Xilai was transferred away,” he told me.

[Bo Xilai, a charismatic and popular figure, was transferred

to Chongqing in 2007 as party secretary to sort out corruption in what is technically the world’s biggest city.

Think of Clint Eastward riding in to town chewing a cheroot and you get some idea of how the media portrayed him and

how the general public have feted him. But, before that, he was Minister of Commerce at state level (2004-2007).

He worked in a provincial position prior to that. The truth of the matter is that Bo Xilai’s

seven year tenure as major of Dalian came to an end on January 2001. So, as good as the good old days were,

it’s a tad unfair to blame Bo Xilai‘s successors for the perceived woes of the past two or three years.]

Now thoroughly confused I continued walking down Zhongshan

Road. A night venue with blaring music sucked me inside. 30 minutes was long enough

for my eardrums, as well as being long enough to convince me that Dalian young people are indeed every bit as upbeat as I

remember them. Despite the cracks in the pavements, the run-down alleyways, and ancient tram system, Dalian

is still one of the most happening cities in China. If the progressiveness of its young people is anything

to go by, Dalian city is right up there vying for the title of China premier league champions. Which reminded me to check out the evaluation criteria for the recent

“China Brand City” contest:

After an hour of fruitless searching, I stumbled on an article

also in the People’s Daily (which cited an article in the China Daily) that succeeded only to muddy

the water. It was essentially a copy of the article I referred to earlier, except that the winner was Hangzhou,

not Dalian (which was listed as one of the nine runners-up, along with Qingdao, Quanzhou, Changchun, Wenzhou, Shenzhen, Changsha,

Wuxi and Tianjin Binhai New area). The Hangzhou city website was also trumpeting the success in the event

that “is billed as the largest and most influential annual competition about city brands in the nation”.

I then wasted another hour trying to get to the bottom of this

mystery, only to hit a dead end at the Brand China Industry Union’s website http://brand.brandcn.com/ which didn’t include any reference

to the event that it had co-hosted. Then, with my patience running out, I hit on an

important lead. The Chinese government’s Intellectual Property Protection in China website reports

that: “On August 8, the 10th Brand China Summit hosted by China Council for the

Promotion of International Trade and Brand China Industry Union was held… Over 2000 governmental officials, representatives

from renowned enterprises, brand experts, brand managers and media participated in the summit. Vice Chairman of both Brand China Industry Union and All-China Federation of Industry

& Commerce Sun Xiaohua made a speech at the summit representing the host. He said Chinese brands have met so many difficulties

in the process of internationalization, with much loss; although this gave us bitter lessons, this is a must in the brand

development. Brand construction is like the growth of a person; we will face confusion and twitch, then span and progress.

These are all necessary. Rome was not built within one day. It needs enterprises' enduring efforts and investments, as well

as pure-hearted expression and charm release of the brands.”

"Curiouser and curiouser," said Alice. This

event was clearly a Chinese-brand event (in line with Brand China Industry Union’s modus operandi) and not a “city-brand”

event. What’s more, according to the government website, the winner was neither Dalian, nor even

Hangzhou… but Wenzhou… the city that is widely recognised as being a stronghold for Chinese brands.

The article points out that “Wenzhou has 203 China Top Brands”.

So, the next time, you are asked to name China’s “best

city”, please be sure to clarify whether you are being asked to name the best "Chinese city-brand”

or best “Chinese-brand city”. And then, just to be on the safe side, agree

the assessment criteria. You will then be in a position to name your top three cities.

|

| Old tram meets new tram on Dalian's Zhongshan Road |

Stepping up the pace Saturday, 28th

August 2010; Xiamen, Fujian

|

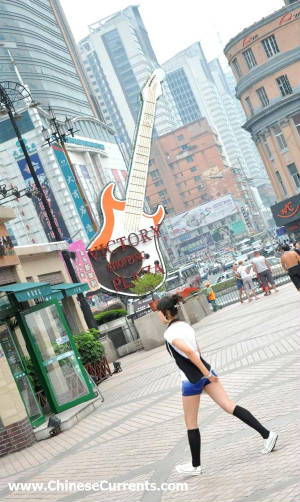

| Nerio Alessandri, striding out in China |

“How much is that one?” I asked. Ms Lin, the sales assistant, went to look at the

price tag. “It’s 169 thousand yuan [about US$25,000]” she told me without

blinking.

“What

does it do for that price?” I enquired.

She

took a deep breath, before reeling off a spec list that seemed to have more to do with a sensory experience centre than a

treadmill. While burning off the calories, the Excite – Technogym’s top of the range model

– also enables you to watch TV, listen to your preferred music, and even smell your favourite smell (thanks to its aroma

diffuser).

“Where’s it made?” I asked. Ms Lin handed me a book that had a smiling Nerio

Alessandri – the founder and chairman of Technogym – on the front cover. “Italian?”

I guessed. A nod of the head signalled that I had guessed right.

I leafed through the thick tome to

glean a few facts (and I would later check the company’s website to find out a few more):

The company – the world’s

second largest manufacturer of fitness equipment – started trading in 1975, but it didn’t make a sale in China

until 1996, when it sold two pieces of equipment to China’s National Space Administration, no less, for use in its training

centre.

According to Marco Treggiari, the managing director of the

company’s Chinese operation (reported by Bloomberg), Technogym now has sales offices in Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou

and Hong Kong, from where it has sold equipment to about 400 gyms (out of the estimated 3,000 that have sprung up in China)

and 210 five-star hotels. Mr Treggiari has estimated that sales in China this year will increase by up

to 30 per cent to US$18 million.

“Do

you have anything cheaper?” I asked.

Ms Lin took me over to the large selection of Shu Hua treadmills, and pointed to

the SH-5167, the second-best seller. “This one is 2,980 yuan [US$440],” she told me.

“And

the best seller?” I asked.

“That’s

the SH-5198, it sells at 4,986 yuan [US$736]”. Ms Lin didn’t want to say how many, but there’s

no doubt that she sells many times more of this product than she does of the Excite – of which she has sold “four

or five” in the 18 months she has worked in the shop.

Shu Hua, which employs a thousand people, is China’s biggest

producer of excercise equipment. The company, which was established in 1996 – the same year

that Technogym began to blaze its own trail in China – is based in Jinjiang, also in Fujian, less than an hour’s

drive to the north of Xiamen. Jinjiang is a city that has become synonymous with the sports industry:

It is reckoned that something in the order of 20 per cent of

sports shoes sold in the world are manufactured there – made by a significant proportion of the several hundred thousand

migrant workers who have flocked to the city in recent years. And more of more of those Jinjiang-made training

shoes are pounding the treadmill machines made by Shu Hua.

Shu Hua’s sales rocketed after it invested heavily in advertising

campaigns featuring Tian Liang, its “Brand Ambassador”. Crowned China’s “Diving Prince” following

his success at the Athens’ Olympics, Tian Liang was a powerful spokesperson for the brand. Even the

controversy surrounding the SH A5210 model which, according to the Beijing Youth Daily, failed a Shanghai government quality

inspection, didn’t dampen the enthusiasm that had been generated.

Zhang Weilian, chairman of Shu Hua,

speaks with evangelical zeal about the company and its mission: “My dream is for every Chinese family

to have a quality treadmill,” he says. Su Hua’s brand vision is equally lofty:

“Chuanbo jiankang, zaofu renlei [promoting healthiness for the benefit of humanity]”

I was puzzled. I

could understand why treadmill sales in many Chinese cities had sky-rocketed (in the many cities with high levels of pollution,

or extreme temperatures and humidity), but why would a fitness-enthusiast living in Xiamen – one of China’s most

“livable cities” – prefer a treadmill to a run on the beach?

I decided to go to the beach

to find out.

It was late afternoon when I arrived at my favourite Xiamen

beach area, which just happens to be near to the giant “One country, two systems” sign that faces the Taiwan-controlled

islands, a few miles away. The

temperature was in the mid 20s, humidity was bearable, and there was a light sea breeze. In short, lovely

conditions for a jog (I am advised).

However, in the two hours I spent there, I saw only one “runner”.

A man in his 60s who was jogging so slowly that people were passing him at walking speed – that was until I tried

to have a word with him, at which point he found a second wind from somewhere and bolted away like an Olympic sprinter.

It

was then that I realised that I should have listened to Ms Lin, who told me that Xiamen people didn’t like running in

public because “It wasn’t convenient”, which I took to be a euphemism for “They feel a bit embarrassed”.

Whatever

the reason, this is good news for the likes of Su Hua and Technogym. It’s also good news for companies

across the Taiwan Straits. In particular it is very good news for Johnson Health Tech Co, Asia’s

largest manufacturer of fitness equipment, which markets its excercise equipment under four brands: Matrix, Vision, Horizon,

and Johnson. The Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou visited the

company earlier this month. He used the visit to impress on a wider audience the benefits of the economic

cooperation framework agreement (ECFA), which is designed to bolster cross-straits economic cooperation by removing trade

barriers and increasing investment. On the 15th August Mr Ma said of Johnson Health Tech:

"One of its products, a portable treadmill that can be folded

and stored under a bed, is innovative and representative of Taiwan's competitiveness".

As far as the likely impact of the

agreement on Taiwanese businesses such as Johnson Heath Tech is concerned, the Taiwanese president, who is a keen jogger, employed

a running analogy: After likening Taiwan's trade barriers to iron shackles that retarded a jogger's stride, Mr Ma went

on to tell the Focus Taiwan News Channel that

"The signing of the ECFA is like

giving that jogger a pair of lightweight sneakers that would help him to run fast”.

However, as with so many of the tangibles that will accrue

from the ECFA, Johnson Health Tech’s stowable treadmill won’t be staring you in the face. For

thousands of satisfied mainland customers, though, it will be a daily reminder that cross-straits cooperation is picking up

pace.

|

| Ms Lin and the US$25,000 treadmill |

Tour of the South Wednesday, 25th

August 2010; Shenzhen, Guangdong

|

| "To get rich is glorious" |

The

state-controlled media called it the Tour of the South.

Or at least they did when they got around to reporting

it, two months after the Tour has been and gone.

At the start of 1992, influential

conservatives in Beijing who were ideologically opposed to the economic reforms that Deng Xiaoping had pioneered in the 80s

– fearing that those reforms would undermine the political status quo – continued to press their foot down on

the economic-development brake pedal.

Deng, believing that “Slow growth equals stagnation and even retrogression”, decided to do everything in

his power to reenergise the reforms. Instead of confronting his critics in Beijing, the 86 year-old master-strategist

climbed on board a train and headed south to the cities that had been the drivers of China’s economic development in

the 80s, where he would urge provincial and local governments to speed up the pace of economic development. His

message was simple: Caution would be disastrous for the country; only ‘boldness’ would result in a bright future.

Or, extending the driving analogy, the message was something akin to: Don’t even think about using the brake,

just put your foot on the accelerator and push it down as far as it will go. The

most significant stage of Deng’s Tour of the South was his visit to Shenzhen, which in 1980 had been declared China’s

first Special Economic Zone (The thirtieth anniversary of the declaration is tomorrow). Shenzhen was the

jewel in the crown of China’s economic development in the 80s, and had very much become the city that developers in

other Chinese cities had looked to for ideas.

And so, at 9am on 19th January 1992, Deng Xiaoping’s train pulled

in to Shenzhen railway station. And the rest, as they say, is history. Over

the years, millions of migrant entrepreneurs have answered Deng’s call to turn Shenzhen into the most vibrant and prosperous

city in China by putting their ‘migration anxiety’ to the back of their minds and focussing, instead, on the carrot

of future wealth.

I am pleased to report that 30 years’ on from Shenzhen’s

opening up, and 18 years after Deng’s world-changing Tour of the South, the Dengesque spirit of ‘fortune favours

the brave’ is as vibrant as it ever was:

“Excuse me. Would you take our photograph?” I

looked around and saw that a young woman was trying to catch my attention by waving a small digital camera in my direction.

I was on my way to a meeting, but had enough time to oblige. She wanted me to take a photograph of her and her friend with a picture of Deng in the

background (poster-size photos of Deng taken during his 1992 visit here are dotted around town). “Where

are you from,” the same woman asked me after I had pressed the shutter release button. “I’m

from Beijing,” I replied. “And you two?” I asked. “We’re

from Nanchang in Jiangxi province. Have you been there?”. They were both surprised to find out that

I had. With the ice now well and truly broken I asked what had brought them to Shenzhen. “I’ve

come here to do business,” replied the woman with the long hair, who was clearly the spokesperson for both of them. “My

mame is Mingming and this is Xixi, she is my best friend – I call her my daughter!”. They both

laughed at the idea (Xixi is 6 months younger than the 20 year-old Mingming). Xixi had to get back to Nanchang

in three days’ time for the start of the new university year. “So

you’re going back to your hometown to study electrical engineering, while Mingming is staying in Shenzhen to make her

fortune,” I joked.

“That’s right!” exclaimed Mingming with a glint

in her eye… “I’ve come here to sell clothes on Taobao.” I am well aware of the popularity of Taobao (often referred to as the “Chinese eBay”) and

was keen to find out how Mingming was going to make money from it. Her plan – to sell Shenzhen-made

clothes and fashion accessories to buyers in Africa – was nothing short of genius: No stock, no overheads, and no risk.

All she had to do was to tailor the stock and the offer to the needs of the target audience she had in mind, and then

develop relationships with the right suppliers (people who would let her post photos of their stock onto her Taobao page).

I surmised that most people she approached would be keen on the proposition, on the basis that – even if they

were already selling on Taobao – the business that Mingming would be generating for them would be incremental.

A true ‘Win-Win’ relationship no less. I congratulated Mingming on her enterprising and well thought through business plan. “But won’t you miss Xixi and your family back in Nanchang?”

I asked.

“Of course I will,”

she replied, “But they understand that I have to grasp this opportunity”. It’s as if Mingming (her name means ‘shining’)

has been inspired by the words of Deng Xiaoping, who said: “An important experience of Shenzhen is the courage to make breakthroughs.

Without a path-breaking spirit, the ‘venturing’ spirit, morale and energy, it is impossible to blaze a trail and

to create a new undertaking.” If you would like to read some more of Deng’s quotes from his 1992 visit to Shenzhen, you are

welcome to click here.

|

| Mingming, Deng Xiaoping, and Xixi |

A breath of fresh air Saturday, 7th

August 2010; Beidaihe, Hebei province

|

| What the boss doesn't see... |

Mao Zedong

loved the place so much that he was moved to write a poem about it. Deng Xiaoping often brought his family

here for their summer holidays.

More than a few state leaders have “grace

and favour” homes here. Many of the big decisions that have shaped modern China have been made here,

not in Beijing (the National Congress pre-meetings were held here for years).

And numerous Beijingers have spent at least a weekend here in the summer and told millions about it.

Of course! It could only be Beidaihe,

a small town on the coast of Hebei province.

If you were the marketing director of Beidaihe’s tourism board, you could be forgiven for thinking

that the job has already been done, and for putting up the “gone for a stroll along one of Beidaihe’s famous sandy

beaches” sign on your office door.

Most visitors who make the 280km trip

from Beijing (in three and a bit hours – if you’re lucky – via the G1 expressway; or two hours via one of

the many scheduled high-speed trains from Beijing’s central railway station) head for the beach. And

today, a Saturday with temperatures here forecast to be ten degrees cooler than in the oven that is Beijing, Beidaihe is bulging

with cars with “jing” number plates and local taxis ferrying Beijingers from the railway station.

The most popular stretch of beach is the Tiger Rocks section,

which costs 8 yuan to enter. Here, people are packed together so tightly that the only sound that can be

heard is the incessant Beijinghua-accented chatter of excited holidaymakers (with a sprinkling of Russian).

If you have come to Beidaihe in search of the sound of the

sea gently lapping onto the shore, then you have chosen the wrong beach. But if, like me, you’re

here for a bucket and spade day with a young child, then it’s the place to be.

And if you’re not quite at the bucket and

spade life stage then, worry not, there are plenty of other beach things you can do with your friends (see photo).

Whatever activity you have in mind, however, make sure it doesn’t involve swinging a cat – there simply

isn’t enough room.

I was determined to get it from the horse’s

mouth as it were – and hear why people, who live in a packed city of about 20 million, endure jammed motorways or a

crowded train to be on a beach that would make a sardine feel claustrophobic. As is often the case in China,

the truth is stranger than fiction:

Mr Hu, a salesperson who worked in Chaoyang, Beijing’s central business district, put his finger

on it: “Here, I really feel free from the pressure,” said Mr Hu, as he took another swig from

the bottle of Yanjing beer (Beijing’s favourite beer brand). “I’m free to do what I like,

when I like, without worrying about work or my clients… I can be myself.”

I mused that the communal sense of this –

thousands of people in the same boat (or, in this case, on the same beach), with most of their clothes off (stripped of the

masquerade of suits and ties… and left with the essence of the “real them” as it were) somehow made the

feeling of “liberation” that bit more intense.

Mr Hu offered me a swig of his beer, as well as inviting me

over to meet his mates from the city. Alas, I had my bucket and spade duty to get back to, so had to decline.

It was

a tempting offer though. As I was walking back through the crowds, I came to the conclusion that wherever

they are, whatever they’re doing, and whatever clothes they’re wearing, there are some things about Beijingers

that will never change: their friendliness and wonderful generosity.

I want one when I grow up Thursday, 5th

August 2010; Beijing

The “walking green man” was suddenly replaced by a static

red one. The woman stopped abruptly. The boy at her side, who had his eyes on other things, continued to walk forward.

The secure grip of the vigilant woman tightened as she pulled the boy back from the road and the menacing cars that had already

begun to speed by. "Look!" scolded the woman, gesturing to the cars that had threatened

to claim yet another young life. The boy was looking, but not at the cars that were now whizzing past his left

ear. He continued looking to his right.

“Beautiful,” said the boy.

“How Cool!”. I glanced over at the subject of his gaze.

He was looking at a motorbike. A big one with extravagant wing mirrors glinting in the sun. I prefer bikes without

engines, so was more impressed by the boy's reaction than by the machine’s presence. "Harley Davidson?" I asked myself. Although,

on closer inspection, it didn’t quite have the “Easy Rider” look of a Harley, which is quite a rare

sight in these parts, but not quite as rare as hen’s teeth (Regular readers of this column – both of you –

may remember that, several months ago, I wrote about a visit I made to a Harley dealership in Beijing.) The boy – who clearly knows more about motorbike

brands than I do – put the record straight: “Jincheng!” he exclaimed. The lights changed, the bike was about to turn left, so I moved back

several yards to be in a position to capture the scene I was witnessing (see photo). Jincheng had been a hot topic several months ago on Chinese blogs

and forums, following the Nanjing company’s participation in this year’s Dakar Rally. The motorsport

event – which moved from Africa to South America (Chile and Argentina) in 2009 – is considered to be the world’s

most gruelling motor race. The move to South America has made it even tougher – not least because five

of the 14 rally stages of the 2010 race passed through Chile’s Atacama desert, which is purported to be the driest place

on Earth. Jincheng sponsored two riders

in the 2010 event – Su Wenmin and Wei Guanghui, both of whom managed to complete the 9,574 km course (despite a number

of mishaps along the way). They finished 75th and 82nd respectively (out of 161 entrants in the class).

The sponsorship of the team is a statement of Jincheng’s global ambitions. According to Dakar.com,

the event’s official website, news from the rally was seen by a staggering 2.2 billion people. As

well as an avalanche of Internet coverage, the 2010 race was broadcast by 80 TV channels to 189 countries. Jincheng

sells 600,000 motorbikes a year, spread across more than a third of those countries, according to its home website.

The company’s country websites – from Africa to South America – trumpet its participation in the

event.

It’s impossible to know how many boys

in Argentina, Chile, Nigeria, or South Africa would react as the boy in Beijing did. Not many I would suspect.

But, there’s no doubt that Jincheng are going out of their way to make an impression and to write a new chapter

in their illustrious history... In

1949, they maintained the aircraft that flew over Chairman Mao’s head during the ceremony at Tiananmen, at which the

founding of the People’s Republic of China was proclaimed.

These days the sound of a Jincheng engine

can be heard by tens of millions of people in 70 countries… as well by the unsuspecting llamas in Chile’s Atacama

desert A source of pride, no doubt, for many of the Chinese boys who, one day,

will be looking to buy the bike of their dreams.

Aftershock Wednesday, 28th

July; Beijing

|

| Emotional journey |

“Will you go to see the film?” I asked Ms Zhou. “Probably

not, it would be too depressing,” she told me earnestly. The memories of 28th July 1976 have cut

just too deep. 34 years ago, Ms Zhou’s world was rocked by the earthquake that struck 11km beneath

the centre of the city of Tangshan in Hebei province. She relives the horror of those 20 seconds:

“I remember the time, it was 3.28am. I was jolted awake. First the floor went up and

down [Ms Zhou mimes the violent up-and-down action with dramatic movements of her right arm]. Then I was

bounced from side to side [she jolts her body from one side to the other as if it is being repeatedly bounced off imaginary

walls]. It was impossible to move forwards. I couldn’t even get to the door”. Ms Zhou and her family were among the lucky ones. They were

far enough from the epicentre (about 60 miles away) and, just as critically, they lived in a house that was sturdily built.

The people in the centre of Tangshan were not so lucky. Photographs of the aftermath show scenes

that are chillingly similar to those taken after the nuclear attack on Hiroshima. The Tangshan earthquake, however, yielded

a destructive power (at least 7.8 on the Richter scale) that was 400 times greater than the atomic bomb that was dropped on

Hiroshima, according to the UN Global Programme for the Integration of Public Administration and the Science of Disasters.

The official number of fatalities is 242,419, which is far fewer than the provincial government’s initial estimate

of 650,000 (about one third of the then-population of Tangshan). Ms Zhou

continues her story: “The people at my town’s earthquake monitoring station knew that the earthquake

was in Tangshan. Very soon afterwards, a medical team on their way to Tangshan came to collect my father,

who was a medical doctor. We had all gathered in our garden, well away from the house, when they arrived.

Later that day, at 6pm, another strong earthquake struck Tangshan. We were all so worried

about my father because we knew he would have been right on top of it. That second quake killed thousands

of rescue workers. The second quake also destroyed the bridge that connected my town to Tangshan.

It was a long time before we were able to find out what had happened to Father. At last we learned

that he and his team had survived the second quake. …He was alive and well and still doing his best

to help some of the [estimated 640,000] injured people. When he came back months later, he told us something

about what he had seen. I will never forget those stories.” Of

the countless stories told by the thousands of people who did live to tell the tale, one of those stories is – a generation

later – being told to many millions of people: Aftershock is the story of the Tangshan earthquake

told from the perspective of a survivor whose mother had condemned her to death by deciding to save her brother instead of

her (the mother had been told by a rescue worker that the slab of concrete that was pinning the two siblings down had to be

moved for one of them to be saved, but that the movement of the slab would kill the other). The girl hears

her mum choosing to save her brother but – unknown to her mother – she later manages to escape the scene. It is a story of reconciliation and of hope as much as it is of recriminations

and despair. The film’s critics say that many important questions have not been asked, let alone

answered. The most obvious of which is “Could more have been done to have reduced the death toll?”

Indeed, the film doesn’t touch on any aspect of Tangshan’s earthquake preparedness (or lack

of it). Why, for instance, was Tangshan unprepared when at least one nearby county, Qinglong, had actually

heeded scientists’ warnings that a strong earthquake was likely to hit the region; and went as far as installing its

own measures to safeguard its population: http://www.globalwatch.org/ungp/qinglong.htm Feng Xiaogang, the director of Aftershock, was asked

if he now considers himself a master filmmaker (in the context of Aftershock becoming the most successful film in

Chinese cinema history in terms of opening day box office receipts – the 36 million yuan it grossed knocked Avatar off

top spot). His reply, published on www.sina.com, provides a revealing insight into the dilemma that affects mainland Chinese directors, particularly those who are responsible

for films that focus on important events that have occurred during the lifetime of a large proportion of the film’s

audience:

“I’m not [a master filmmaker].

This is not an era that can produce masters. …Because we [directors] face too many danger points.

…You can’t get too close to these danger points. You can’t just casually cross the stream. You have

to jump from this rock to that rock and carefully try to move forward. …But sometimes there is no

rock, and then you have to make a detour, because, if you just jump into the water, you might drown.”

|

| Tangshan, Hebei province, following the earthquake of 28th July 1976 |

Rebecca makes World Cup debut Friday, 11th June

2010; Xuchang, Henan province

|

| Don't worry it's Dragon Proof |

Xuchang! The final stop on a nine day tour that

began on June 3rd in Taiyuan, the capital of Shanxi province. From there I flew to Lanzhou, the capital

of Gansu province, for a three-night stay. On Monday, I flew to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province,

before travelling three hours by road to the prefecture-level city of Mianyang. Then, back to Chengdu for

yesterday’s flight to Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, from where I travelled directly from the airport to

the prefecture-level city of Xuchang.

I must admit that when I saw Xuchang

on my travel itinerary, I raised an eyebrow. “Where’s that,” I asked. The

person I asked wasn’t sure. “It’s in Henan province… or, then again, it might

be in Hunan,” was the reply. Their uncertainty made me feel a little better about having no idea

which province it was in. Before I go anywhere “new”, I usually

spend quite a while learning as much as I can about the place I’m planning to go to. However, on

this occasion, other than working out that Xuchang is “not far from Zhengzhou”, in Henan province, I simply didn’t

have time to find out more. So, I’m embarrassed to admit, I arrived in

the city without knowing the first thing about the city. In these situations it pays to go for a walk and to find some local

people to talk to. I met Mr Ma, who was selling fruit near to the hotel I was staying at. “Hi, I’ve just arrived in the city,” I said, “I wonder

if you wouldn’t mind telling me something about the place?” Mr Ma looked at me as if I had

just stepped out of a spaceship. I tried a different approach: “What’s Xuchang famous for?”

I asked. “Xuchang,” used to be an ancient capital,” said

Mr Ma without any hint of pride.

“Great,” I said.

“Where can I see the ancient sites,” I enquired. “There

aren’t any,” said Mr Ma. He shook his head. “No, not a thing.” [On returning to Beijing I would find out that in 220AD Xuchang was declared the

capital of the newly-formed “kingdom” of Wei, one of the Three Kingdoms, which were each ruled by an emperor who

claimed to have the mandate of heaven (the right to rule) by dint of his superior lineage, connecting him to the last emperor

of the deposed Han dynasty. For some reason, after only a couple of years in Xuchang, the Wei emperor moved

his court to Luoyang (also in modern day Henan) – which, unlike Xuchang, does have some excellent ancient sites to look

around. Oh yes, I also found out that modern day Xuchang has a population of 4.5 million. And that the

city is twinned with Ambo in Ethiopia although, with due respect to the city of Ambo, that wasn’t the top of mind answer

when I asked Xuchang people what their city is famous for.] I thanked

Mr Ma for the information and moved into the backstreets of the older part of town to find out more. A