|

Joseph Needham and 'Brand China'

|

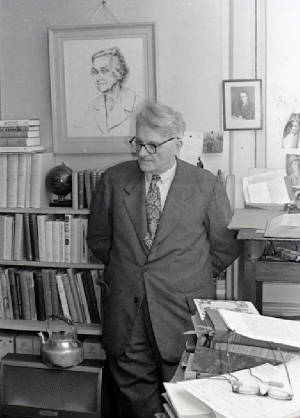

| Joseph Needham in his study, Cambridge University, 1965 |

Mention ‘China’ and ‘science and technology’ in the same breath to someone, and what kind

of response are you likely to get?

These days, ‘innovative’, and ‘advanced’ are two of the words that might trip off

the tongue. Quite a difference from, say, 20 years ago, when ‘copycat’, ‘laggard’, and perhaps lots

of head-scratching may well have been the typical response. By any measure, the rapidity of

China’s progress in science and technology in the last two decades has been nothing short of astounding. The rest of

the world’s view of China’s development in this field has been informed by writers, analysts, academics and –

most significantly – by people’s own views of China’s brands and, of course, of the country itself.

In 2018, ‘foreign-tourists’ made 30.5 million visits to mainland China; an increase of almost

five per cent compared with 2017. Many of those visitors avidly shared their impressions of China to friends, family, and

colleagues via word-of-mouth and the numerous social-media channels. Consequently, hundreds of millions

of people all over the world are hearing about China’s impressive modernity from people who have experienced the airports,

the high-speed rail network, the subway systems, the 4 and increasingly 5G connectivity, the electric-vehicles and the ‘cashlessness’

themselves. The burgeoning fascination for all things Chinese has spurred a wave of interest

in Chinese history. One of the popular subjects in this genre is ancient China’s technological superiority. Long-overdue

news of China’s ‘four great inventions’ [si da faming] – paper making, printing, gunpowder,

and the compass – has at last reached large numbers of people in the Western world. To the extent that, these days,

any half-decent pub quiz team would be expected to know all the names of the ‘four-greats’.

The story has travelled far and wide. But, as is so often the case with stories, very few people know the

name of the storyteller. This would not have worried Joseph Needham (1900-1995) in the slightest.

He was fully focused on one, albeit Herculean task: To give China the long-overdue respect it deserves for its scientific

contributions to humankind. Joseph Needham studied biochemistry at the University of Cambridge

under the tutelage of Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins, who would be jointly-awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

in 1929. Needham was a brilliant student and equally exceptional researcher, who would go on to author more than 100 scientific

publications between 1921 and 1942. A Harvard reviewer was so impressed by one of those publications,

a book titled Biochemistry and Morphogenesis, he or she was moved to write: “[It] will go down in the annals

of science as Joseph Needham’s magnum opus, destined to take its place as one of the most truly epoch-making books in

biology since Charles Darwin.” Surely, then, it would only be a matter of time

before he followed Sir Frederick’s path all the way to the Nobel rostrum. Perhaps

he would have, had he not met Lu Gwei-Djen (Lu Guizhen), also a biochemist at Cambridge. She had arrived there in 1937 to

pursue post-graduate studies, after fleeing from war-torn Shanghai.

Lu ignited his intense passion for studying Chinese characters, which he went on to describe as, “…A

liberation, like going for a swim on a hot day. [For it gets you] entirely out of the prison of alphabetical words and into

the glittering, crystalline world of ideographic characters.” Lu, whose father was a distinguished Nanjing pharmacist,

also fired Doctor Needham’s fanatical interest in China’s long and illustrious history in numerous fields of science.

Informed by professor Luo Zhongshu, who was close to scientists in Chengdu (beyond the

vast territory occupied by Japanese forces), he realised that China’s scientific institutions were in a parlous state.

Determined to help, he persuaded the British government that he should

be its man in charge of the British Scientific Mission in China. By 1946, he and his team of 10 Chinese and six British scientists

had visited 296 ‘places of learning’ on journeys totalling many thousands of difficult miles. During this grand tour of schools, universities, laboratories, and industrial units, the work of this small

team resulted in the provision of ‘tons of scientific equipment’ as well as some 7,000 science books.

Many scientists and others he met were keen to talk about China’s incredible science history. They also

introduced him to the literature that provided the all-important evidence that supported the many wondrous stories.

In the ‘Acknowledgements’ [Preface, page 11] of the first volume of Science and Civilisation

in China [1954], Joseph Needham would write, “The work gave unimagined opportunities for acquiring an orientation

into Chinese literature of scientific and technical interest, for in every university and not a few industrial installations,

there were scientists, doctors and engineers who had themselves been interested in the history of science, and who were not

only able but generously willing to guide my steps in the right paths.”

The

longest of the physical ‘steps’ towards his enlightenment was a four-month expedition from Chongqing to the ancient

Mogao Grottoes, also known as the ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas’, near Dunhuang, Gansu province.

Surrounded by boundless desert, the small ‘oasis town’ of Dunhuang became an important site for

merchants traversing the ‘southern section’ of the Silk Road – the ancient superhighway between China and

the Western world. In the 1,000 years that followed the excavation of the first grottoes in

the 4th century AD by Buddhist monks, the Mogao Grottoes developed into one of the Buddhist world’s greatest cultural

sites. Mogao became a staging post for the spread of Buddhism from India to China; as well as the place where Chinese monks

could worship and meditate, before continuing their ‘Journey to the West’. For Joseph Needham, also, this was as much a spiritual

journey as it was an arduous physical one. His quest was to see with his own eyes the place where the Diamond Sutra was ‘discovered’

a few decades before. This document, found in the ‘Library Cave’, is regarded as one of the most important artefacts

in the history of science. Remarkably, it is precisely dated. The date that appears on the sutra

corresponds to the 11th May 868 in the Gregorian calendar. Even more remarkable is that it

was not hand-drawn. It was printed… …587 years before Johannes Gutenberg printed

the Bible in Germany [1455]; and 608 years before William Caxton published The Canterbury Tales, England’s first printed

book [1476]. Recorded on the Diamond Sutra is the Chinese translation of a ‘question

and answer’ dialogue between a disciple, Subhüti, and the Buddha. An alternative name of this sutra, ‘The

Perfection of Wisdom Text that Cuts Like a Thunderbolt,’ seems entirely fitting as well as prophetic in that, more

than any other, this was the ‘China first’ that had inspired Joseph Needham to embark on what would be a more

than 50-year mission to persuade the world that China had been the home of the world’s most advanced ancient civilisation

by far.

His experiences and rich encounters during the numerous journeys that followed the ‘Dunhuang Expedition’

would convince him that the plan to write a “single slim volume” on the history of science in China needed to

be re-thought: “During my time in China I realised that one volume would not be enough, and that it would probably

have to be seven,” he wrote. Back in Cambridge, Joseph Needham began to type the pages that

would become the monumental Science and

Civilisation in China. He was surrounded

by mountains of beloved books from numerous Chinese sources. A kid in the world’s biggest and best sweet shop:

What a cave of glittering treasures was opened up! …One after another, extraordinary inventions and

discoveries clearly appeared… often, indeed generally, long preceding the parallel, or adopted inventions and discoveries

of Europe. …Wherever one looked, there was ‘first’ after ‘first.’” Indeed,

there were so many ‘firsts’ after ‘firsts’, that, although the plan for seven volumes didn’t

change, volumes 4 to 7 were split into 24 parts. Several of these were completed by academics from the Needham Research Institute and published after his death in 1995. The final book in the collection, Science and

Civilisation in China, Volume 7, Part II: General Conclusions and Reflections, lists the 262 ‘firsts’ that

were described in earlier volumes of the work. But, why then didn’t China go on to develop

‘modern science’ before the ‘industrial revolution’ in Europe, instead of seemingly running out of

creative steam at around 1500 AD? This is known as the ‘Needham Question’. A Google search for the term and ‘1500 AD’ yielded 4,230 results, including links to numerous

attempts to provide possible answers. Here’s one more: Could

it be that, after four millennia of frenzied activity, the Chinese Dragon had simply decided to take a well-deserved nap?

It’s worth remembering that, for Chinese Dragons, 500 years is but a blink of an eye.

PLAY the PODCAST

References Agar, John (2012). ‘It’s Springtime for Science’: Reviewing China-UK Scientific Relations

in the 1970s. Notes and Records of The Royal Society, (2013) 67, 7–24. Blue,

Gregory (1997). Joseph Needham – A Publication History. Chinese Science 14 (1997): 90-132.

Davids,

Karel (2016). Religion and technological development in China and Europe between about 700 and 1800. Artefact Techniques,

histoire et sciences humaines. Dimaculangan, Pierre (2014). The Needham Question and the Great Divergence:

Why China Fell Behind the West and Lost the Race in Ushering the World into the Industrial Revolution and Modernity.

Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 71 : No. 71 , Article 10. Elman, Benjamin (2007). China and the World History

of Science, 1450-1770. Education About Asia, Volume 12, Number 1, Spring 2007. Finlay,

Robert (2000). China, the West, and World History in Joseph Needham's ‘Science and Civilisation in China’.

In the Journal of World History, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 265-303. University of Hawaii Press. Goldstone, Jack (2009). Why

Europe? The Rise of the West in World History, 1500-1850. McGraw-Hill. Goldsmith, Maurice (1995). Joseph

Needham: 2Oth-Century Renaissance Man. Unesco Publishing. Google (2019). Search results for the “Needham

Question” yielded 4,230 results (at 6pm Beijing time on the 27th October 2019). Gurdon J. and Rodbard, Barbara (2000).

Joseph Needham, C.H. 9 December 1900 — 24 March 1995. Biographical Memoirs of the Fellows of the Royal Society.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbm.1999.0091 accessed on the 19th October 2019.

Jun, Wenren (2013). Ancient Chinese Encyclopaedia of Technology: Translation and Annotation of the Kaogong

ji (The Artificers' Record). Routledge. Lee, Lily Xiao Hong, ed. (2003). Biographical Dictionary

of Chinese Women: The Twentieth Century 1912-2000, pp 382-384. An East Gate Book. Mei

J. (2019). Some Reflections on Joseph Needham's Intellectual Heritage. In Technology and Culture, Volume 60, Number

2, April 2019, pp. 594-603 (Article). Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People's Republic of China.

Tourism data 2018 and 2017, via https://www.travelchinaguide.com/tourism/2018statistics/ accessed on the 23rd October 2019. Montgomery,

Laszlo (2015), Joseph Needham Part 1. The China History Podcast, number 155. https://www.teacup.media/2015/07/14/chp-155-joseph-needham-part-1/ Montgomery, Laszlo (2015), Joseph Needham

Part 2. The China History Podcast, Number 156. https://www.teacup.media/2015/07/14/chp-156-joseph-needham-part-2/ Mougey, Thomas (2017). Needham at the

crossroads: history, politics and international science in wartime China (1942–1946). In The British Journal for

the History of Science, Volume 50, Issue 1, pp 83–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087417000036 accessed on the 20th October 2019. Needham, Joseph (1943), representing the British Council Cultural Scientific Mission in China. Science

in Chungking. In Nature. July 17 1943, volume 152. Needham, Joseph (1943), representing

the British Scientific Mission in China. Science in Western Szechuan. In Nature. October 2 1943, volume 152, pp 372-374.

Needham, Joseph (1943). Journal written by Joseph Needham of his journey through northwest China to Dunhuang

between August-December 1943 (unpublished manuscript, 71pp. with four inserts). The Needham Research Institute, Cambridge:

NRI2/5/12/1. Needham, Joseph (1946), representing the British Scientific Mission in

China. Science and Technology in China’s Far South. In Nature. February 16 1946, volume 157, pp 177-179.

Needham, Joseph (1946). In the Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Joseph

Needham CH FRS (1900-1995), biochemist and historian of science. Cambridge University Library: Department of Manuscripts

and University Archives. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/87f77d01-d7c9-407d-a0fd-c139512e65a3 accessed on the 21st October 2019. Needham, Joseph (1949). Central Asia and the history of science and technology. In the Journal of

The Royal Central Asian Society, 36:2, 135-145. Needham, Joseph (1954) with the research assistance of Wang Ling. Science

and Civilisation in China, Volume 1: Introductory Orientations. Cambridge At The University Press.

Needham,

Joseph and Hartley Harold Brewer (1962). Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins, O.M., F. R. S. (1861-1947) Centenary Lecture held

on 20 November 1961 in the University of Cambridge. In The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, 31st December

1962, volume 17, issue 2, pp116-162. Needham, Joseph (2004) with the collaboration of and contributions by Kenneth

Girdwood Robinson and Ray Huang (Huang Jen-yu). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 7, Part II: General Conclusions

and Reflections. Cambridge University Press. Raj, Kapil (2016). Rescuing

Science from Civilisation: On Joseph Needham’s “Asiatic Mode of (Knowledge) Production. In Arun Bala and

Prasenjit Duara, eds. The Bright Dark Ages: Comparative and Connective Perspectives. Brill, Leiden/Boston.

Sima, William (2015). Diplomat and Scholar: Frederic Eggleston in Chungking and Canberra, in 1941–1946.

In China and ANU [Australian National University]: Diplomats, Adventurers, Scholars. ANU Press, pp 35-62 [Chapter 2].

The British Library https://www.bl.uk/people/william-caxton [accessed on the 26th October 2019, “The

earliest book he printed in England”]; and https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/william-caxton-and-canterbury-tales [accessed on the 25th October 2018: “The Canterbury

Tales... first published in 1476”]. The Economist (2008). Question

marks. Why did China’s scientific innovation, once so advanced, suddenly collapse? A British academic made this question

his life’s work. Print edition, 5th June 2008. Wang Da-Jun (2005). Bell Chime, Dragon Washbasin:

Modern Scientific Information Hidden in Ancient Chinese Science and Technology. Technische Mechanik, 2005, 9-16.

Whitfield, Roderick et al (2015). Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art History on the Silk Road,

Second Edition. Getty Publications. Winchester, Simon. (2008). The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of

the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom. Harper. Zhang, Baichun and Tian Miao (2019).

Joseph Needham's Research on Chinese Machines in the Cross-Cultural History of Science and Technology. Technology

and Culture, Volume 60, Number 2, April 2019, pp. 616-624 (Article). Johns Hopkins University Press Zhang, Yaguang

et al (2015). Economic Cycles in Ancient China. Working Paper 21672. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge,

Massachusetts, USA. Photos Photo of Joseph Needham in his study

at Cambridge University, 1965. By courtesy of Kognos. Creative Commons license; details: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joseph_Needham_in_Cambridge_1965_04.jpg Photo of

a section of ‘The Caves of a Thousand Buddhas’, Mogao, Dunhuang, Gansu Province, taken by Steve Bale at 3.43pm

on the 24th July 2015.

|