|

|

| Playing his part in China's success |

For

many in their 40s, the thought of a jog around the park is enough to cause a hot sweat. And then there’s

Li Ning, who at the age of 44, is able to fly through the air and then “run” a lap around the Birds Nest’s

vertical wall-of-death in front of, according to the China Daily at least, a television audience of “some four billion”

people (including more than half of the total Chinese population). Li Ning, already a household name in

China for the past 24 years, was chosen to run the anchor leg of the torch relay at the most-viewed opening ceremony in Olympic

history, and in so doing to become one of the very few Chinese sportsmen to be known by millions outside of China.

Mr Li, as many now know, won 3 gold medals during the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, as well as another three medals

made of less-precious metals – the most decorated athlete of the 1984 Games. It was an astonishing performance of truly

historical significance: ’84 was the first time that China had entered an Olympic team of more than two (in the 1932

Olympics, also in Los Angeles, Fu Baolu polevaulted 3.2 metres and Liu Changchun was eliminated in the preliminary heats of

the 100m and 200m). China’s only other appearance prior to ’84 was in Helsinki in 1952, when

a single competitor, Wu Chuanyu, swam without any trace of a medal.

Mr Li’s history-making achievements were amplified to the point of frenzy by an 80s-media hungry for evidence

of China’s ability to succeed on the world stage. The news from afar sank deep into the hearts of

Chinese people. So deep in fact that everyone over forty, it seems, is still able to remember where they

were and who they were with when his medals were rolling in. Since then they have called him the “Gymnastics

Prince”. Talking of

princes, his life story is the stuff of which rags to riches fairytales are made. He was born in 1963 in

Guilin in Guangxi Autonomous Region, one of the poorest regions of China. His potential was spotted by

state scouts at the age of eight and he was selected to join a government-run training school, where the rigorous regime would

groom him for super-stardom. After his retirement from gymnastics,

Mr Li set his sights on gold of a different kind. In May 1990 he founded the Li-Ning sportswear company,

and the rest, as they say, is history.

|

|

|

| Front page of the China Daily's Olympic Games supplement |

Throughout

his life, Mr Li has relished new challenges. Not content with sitting back and watching the gold coins

roll in, he set about a new training regime that would take his business to an entirely different level. He

read law at Peking University. But that was merely phase one of his preparation. He

said in 1998: “After finishing my undergraduate studies, I’ll

continue my studies, but in the MBA programme… I am preparing myself for competition on the global

market.” After graduating with an MBA, the Gymnastics Prince

then implemented ambitious growth plans that would make him a corporate king. According

to the Li-Ning 2007 financial report, Mr Li is chairman and 36% stakeholder in a company that has over five thousand retail

outlets in China. Li-Ning’s tills rang up more than 4.35 billion yuan of revenue – up 36.7

per cent year-on-year; and the company made an operating profit of 682 million yuan (up an even healthier 51.5 per cent during

the same period). Revenue from footwear alone was 1.86 billion. Which means

that – at an average price-per-pair of, say, 250 yuan – somewhere in the region of seven and a half million people

(mostly young Chinese) bought a pair of “Li Nings” last year. Now that’s a lot of feet

sporting a huge amount of “brand-presence”. Certainly in lower-tier China, Li Ning’s

distribution chain extends much further than its competitors. The truth of the matter, though, is that

many of the people who buy Li-Ning are not quite as well-heeled as their international-brand-buying counterparts. Just as

worrying for the brand, Nike and Adidas are now encroaching on areas of China where, up until recently, they had reigned supreme.

For many, Li-Ning is the compromise choice: the choice of those who aspire to buy a genuine pair of Adidas, Nikes,

or Pumas, but can’t afford it. Li Ning is acutely aware of this, and has been

working hard to improve his brand’s image. Being seen as a world-player is, for Li-Ning, an important

part of this strategy. Hence the various sponsorship deals with foreign teams, such as the Spanish Olympic

Team, the US table tennis team; and deals with foreign sports stars. Dilemmas surface, however, when foreign

teams sponsored by Li-Ning beat China’s very own – as happened when the Li-Ning kitted Spanish men’s basketball

team beat the Chinese team in the second game of the preliminary round of the Olympic competition (two days earlier, Yao Ming

and the rest of the China-stars had succumbed to the Nike-shirted US “redeem team”). Any viewers,

or blog-writing Chinese, who had been pondering the irony of the brand’s sponsorship strategy would have forgotten all

about the issue the following day, though, when the Chinese men’s gymnastics team thrilled the nation with a magnificent

gold medal winning performance, easily beating sliver-medalists Japan, their former nemesis. The victorious

China team was sponsored by Li-Ning, whose logo was emblazoned across the vests of the six now-national-heroes.

The competition and medal ceremony featured lots of close-ups of the Li-Ning logo and was repeated across the main

TV channels, ensuring that most of the adult population of China could see it. Li Xiaopeng, who won

the vault section of the competition, took his personal tally of gold medals won in major global competitions to 15 –

one more than Li Ning could garner. But, far from blowing his own trumpet, the young Mr Li only wanted

to talk about the older Mr Li’s achievements: "I think Li Ning is a miracle of his time and I cannot exceed him,"

said the young Mr Li. Li Ning, who was there to cheer on his boys,

would have no doubt been impressed by his namesake’s modesty. You win some; you lose some (sometimes against

your own side). Sport sponsorship, then, is full of uncertainties and contradictions. But

one thing is for sure, in the hotbed of country versus country competition, any sports brand that feeds off national pride

must be careful who it sponsors. It’s hard to see how Li-Ning can have it both ways.

What if, horror of horrors, the Li-Ning wearing US men’s table tennis team beat the Li-Ning wearing Chinese team?

|

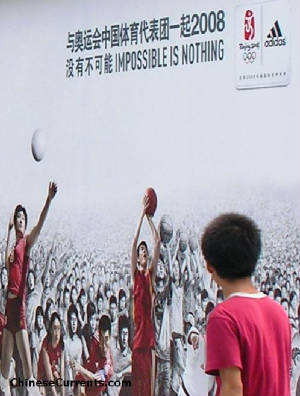

| ...somethings are more possible than others |

The unannounced theme of the opening ceremony was “Chinese achievement”, and Li Ning was held up (literally)

as the personification of the success of modern China (the climactic chapter in the history show that was played out).

By lighting the Olympic cauldron in the manner he did, Li Ning set millions of patriotic pulses racing. The spectacle also inspired

thousands of writers to cast their votes on the rights and wrongs of inviting the man-brand to make such an impact –

in light of Adidas’s “exclusive” (sportswear) zillion-yuan sponsorship of the Beijing Olympics. The sixty-four zillion

yuan question is, though, just what will be the longer term impact of what some pundits are calling the world’s biggest

guerrilla (or ambush) marketing coup? If this was a marketing coup, then it was neither a guerrilla raid nor an ambush.

No, this was no smash-and-grab under cover of darkness; it was more like a full-frontal in-your-face flag-waving bugle-sounding

charge. But,

coup or not, should it have been allowed? It would be mean-spirited, not to mention plain wrong to argue that Li Ning’s credentials

for the job of running the final leg were not far better than any of the other candidates'. And he was wearing an Adidas

China-team shirt. But, then again, that probably wasn’t much comfort for the assembled executives of the official

sponsor of the sportswear category. No matter how hard you argue, you can’t separate the person from the eponymous brand; and

therefore, no matter what the rights and wrongs may be, Adidas were eclipsed, and Li-Ning has received a huge boost.

Just how long that

boost will last, however, remains to be seen. Those responsible for Adidas and Nike marketing must be concerned that Li-Ning might

set about leveraging that historic moment for all it is worth, by focusing all its investment and activities on cementing

its association with national pride and ambition, and establishing itself as the brand that is synonymous with "Brand

China". Foreign

ambitions can be a fine thing but, for Li-Ning, China is where the battleground is (in 2007, less than one per cent of Li-Ning’s

revenue came from foreign sales – a decline compared with 2006). Li-Ning’s sponsorship of the Argentine

men’s basketball team, and the lavish TV and website “Anything is possible” commercial it produced, could

do wonders for Li-Ning sales in Buenos Aries perhaps. But this is a distraction and moves the brand further away from

its natural heartland. The loosening, no matter how slight, of the emotional bond with its home audience has been manna

from heaven for Adidas, which has been winning the hearts and minds of millions of Chinese with its “Impossible is nothing”

advertising campaign. The award-winning ads recognise the contribution that ordinary Chinese people make to the success

of their national teams. (Funnily enough, Li-Nings tagline, “Anything is possible”, which predates Adidas's

line, would also work very well for this campaign.) I was in the Adidas “village”

in Sanlitun, Beijing, a few hours before Li Ning lit-up the night sky (along with a cauldron of controversy), and spoke to

some young people about the Adidas brand. Yang Wei, a university student from Beijing, was waiting to find out how quickly

he could react to the starter’s gun (having donned a new pair of running shoes, which Adidas were lending-out for

the “race”): “I would love to buy a pair of Adidas trainers”,

he said, “…But I can’t afford it”. I don’t know how much the young Mr Yang’s view of Adidas

has changed following Li Ning’s guest appearance at the opening ceremony. But, these things take time, money and, of

course, the right strategy to drive home the home-brand’s unique advantage. Talking of money, the acid test will of

course be when Mr Yang's disposable income has risen to the level at which he, and the millions like him, can choose the brand

that's closest to the heart.

|

| China is quickest out of the starting blocks. A portent of success? |

| Li Ning infocommercial |

|

| Adidas Olympic ad |

|

|